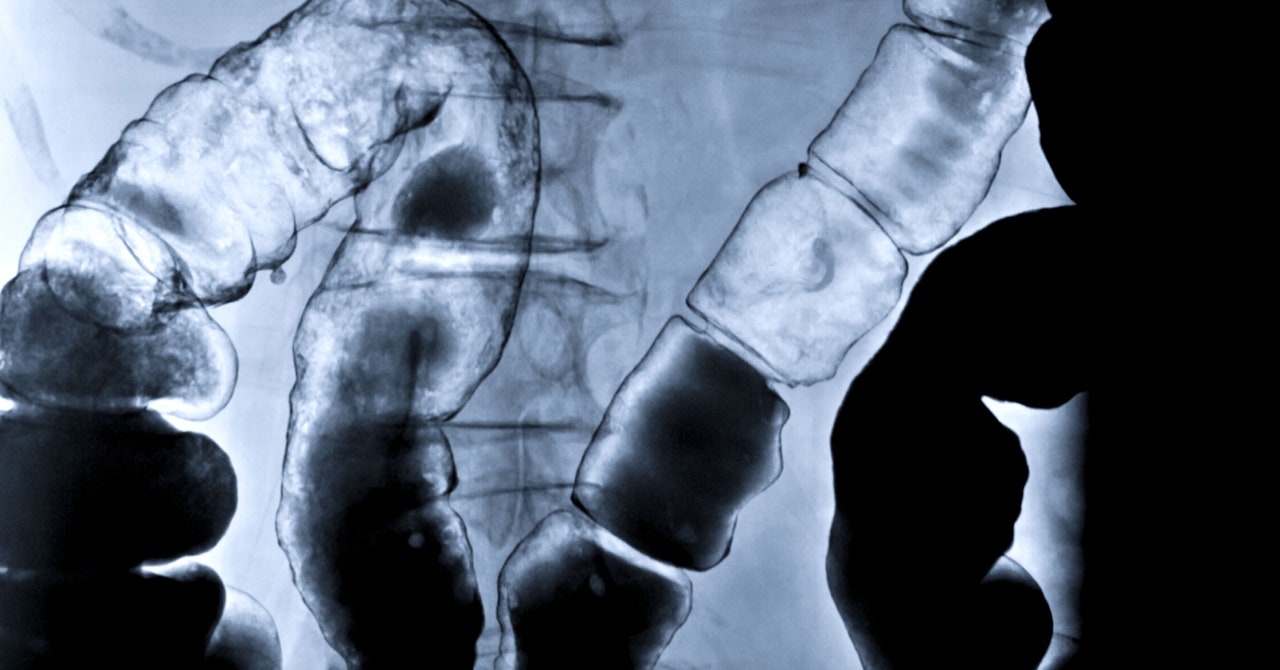

Your gut has an obvious job: It processes the food you eat. But it has another important function: It protects you from the bacteria, viruses, or allergens you ingest along with that food. “The largest part of the immune system in humans is the GI tract, and our biggest exposure to the world is what we put in our mouth,” says Michael Helmrath, a pediatric surgeon at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center who treats patients with intestinal diseases.

Sometimes this system malfunctions or doesn’t develop properly, which can lead to gastrointestinal conditions like ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and celiac—all of which are on the rise worldwide. Studying these conditions in animals can only tell us so much, since their diets and immune systems are very different from ours.

In search of a better method, last week Helmrath and his colleagues announced in the journal Nature Biotechnology that they had transplanted tiny, three-dimensional balls of human intestinal tissue into mice. After several weeks, these spheres—known as organoids—developed key features of the human immune system. The model could be used to mimic the human intestinal system without having to experiment on sick patients.

The experiment is a dramatic follow-up from 2010, when researchers at Cincinnati Children’s became the first in the world to create a working intestine organoid—but their initial model was a simpler version in a lab dish. A few years later, Helmrath says, they realized “we needed it to become more like human tissue.”

Scientists elsewhere are growing similar miniature replicas of other human organs—including the brain, lung, and liver—to better understand how they develop normally and how things go awry to give rise to disease. Organoids are also being used as human avatars for drug testing. Since they contain human cells and display some of the same structures and functions as real organs, some researchers think they’re a better stand-in than lab animals.

“It’s incredibly important that when we are trying to create these platforms for testing drug efficacy and drug side effects in human tissue models that we actually make sure that we are as close to, and as complete as, the tissue in which the drug will work eventually in our human body. So, adding the immune system is an important part of that,” says Pradipta Ghosh, director of the Humanoid Center of Research Excellence at the University of California San Diego School, which is developing human organoids to screen and test drugs. Ghosh was not involved in the study.

To grow the organoid, the scientists started with induced pluripotent stem cells, which are created from mature human cells drawn from blood or skin. These have the ability to turn into any type of body tissue. By feeding the stem cells a specific molecular cocktail, the team coaxed them into intestinal cells. After growing for 28 days in a dish, the cells formed spheres of tissue just a few millimeters in diameter.

The team carefully transplanted these spheres into mice that had been genetically engineered to suppress their own immune systems so that the organoid tissue would not be rejected. (The researchers transplanted the intestinal organoid next to each mouse’s kidneys, so it wasn’t actually connected to the animals’ digestive tracts.) To stimulate the organoids into producing human immune cells, they had previously given the mice human cord blood—a source of stem cells that could transform into the desired cells.