Hossen, Sheehan, and their colleagues modeled how well a cargo-ship-based sensing array might actually work. Hossen is the first author on their paper published in Earth and Space Science in February, evaluating ship-borne GPS tsunami forecasting in the Cascadia subduction zone via a computer simulation. Given the region’s steady vessel traffic, the researchers used actual ship coordinates supplied by the global data and analytics provider Spire. While marine traffic typically follows similar routes, the number and spatial distribution of ships varies, which the simulation took into account. The study also simulated tsunami-produced variations in ship elevation and velocity. The team used data assimilation, a technique that combines observations with a numerical model to improve predictions, in order to forecast the virtual tsunamis.

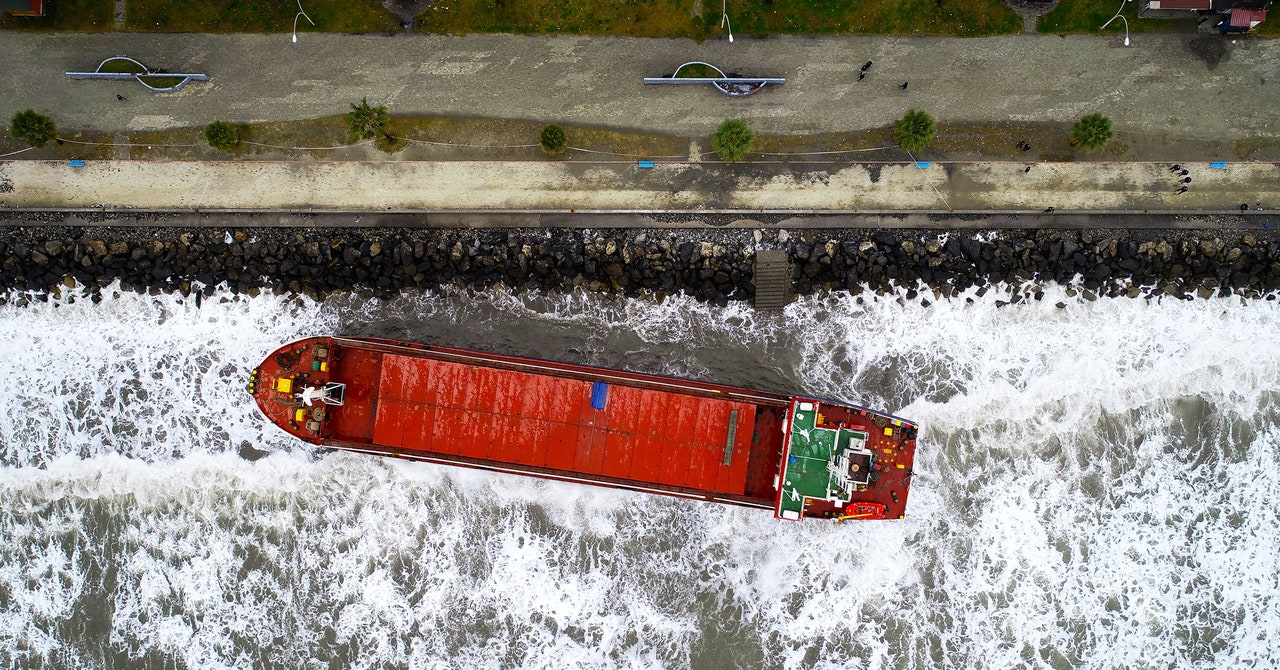

Supposing each ship was equipped with a GPS sensor that could precisely measure elevation (and therefore detect a passing tsunami), the simulation indicated that a 20 kilometer gap—about 12 miles—between vessels in areas with high ship density would be sufficient to make accurate forecasts and that predictions can be made reliably within 15 minutes of tsunami onset.

And that matters because the Pacific coast is due for some sizable tectonic activity from pressure buildup, according to scientists. “In the Cascadia subduction zone region, many studies show that a big earthquake is coming,” says Hossen. “We don’t know when and where it could trigger a tsunami.”

But this system wouldn’t be ready to go right away. While commercial ships routinely use GPS, they don’t report their elevation data—exactly how much they’re bobbing. Around the globe, the Automatic Identification System (AIS) continuously tracks their latitude and longitude, but these broadcasts don’t include elevation, since boats presumably stay at sea level. To detect tsunamis, these slight changes in elevation would have to be relayed in real time, but given satellite navigation’s ubiquity, including this information may be feasible.

“What I really liked about this method is that the method is cheap,” says Anne Bécel, the Lamont Associate Research Professor in the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, who was not involved with the CU Boulder study. “If this method is fully developed, it would become very affordable for many countries that are threatened by local tsunamis.”

Commercial vessels could complement, not replace, existing tsunami detection mechanisms, while offering a much more cost-effective approach than adding new seafloor pressure sensors. While ships using GPS could help predict a tsunami’s threat by recording wave height, which correlates with its damage potential, they wouldn’t necessarily sound the alarm that a tsunami had been generated, says the University of Stuttgart’s Foster. “This system is never likely to be the thing that triggers the alarm. It’s going to be the fact that there was a huge earthquake that triggers the alarm,” he says.

Still, other geologic events—such as submarine landslides and volcanic eruptions—can cause tsunamis. A warning system based only on wave observations, and not on what triggered them, would be advantageous, says Sheehan, who’s also a fellow at CIRES. “With this method, we’re not assuming really anything about the earthquake or the landslide or about whatever causes the tsunami. We’re just looking at the waves as they are recorded by the ships, so you’re using the actual observations,” she says.

Foster says that shipping companies have been very receptive to the idea of using their boats to help forecast tsunamis. But before that can happen, scientists will need to do more research on the extent of the floating network that will be needed, as well as the precision and processing of ship-based GPS data.

While the CU Boulder study relied on a simulation, adding further data from real ships could enhance the findings, Bécel says. “The next step will really have to show that, with high-precision GPS, [researchers] have the same results with high accuracy,” she says. “Right now it looks like it’s very promising.”

More Great WIRED Stories