On Monday, the US Food and Drug Administration granted approval to a keenly-watched Alzheimer’s drug, aducanumab, developed by the drugmaker Biogen. The decision to approve the drug, which was once abandoned as a failure, has been the subject of debate within the scientific and regulatory community for months.

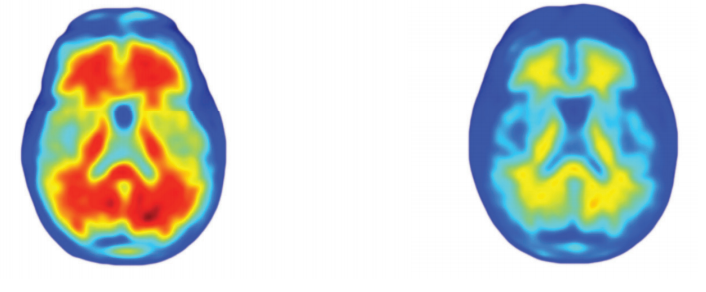

Aducanumab, which will be marketed as Aduhelm, is the first novel Alzheimer’s treatment to be approved since 2003, the FDA noted in a press release. Aducanumab is also the first novel treatment designed to address one of several proposed underlying causes of Alzheimer’s: the buildup of beta-amyloid plaques in the brain that disrupt the communication of neurons.

Critically, the drug received a conditional form of FDA approval called the ‘Accelerated Approval Program.’ The accelerated approval pathway is designed to provide early access to drugs for serious conditions if they address markers of disease – even when the FDA has misgivings about the overall results of clinical trials. Because of this, Biogen will still have to conduct a post-approval confirmatory trial of aducanumab.

“If the drug does not work as intended, we can take steps to remove it from the market. But hopefully, we will see further evidence of benefit in the clinical trial and as greater numbers of people receive Aduhelm,” the FDA statement reads.

TechCrunch has contacted Biogen for comment on the upcoming confirmatory trial, and will update this story with Biogen’s response.

The use of the accelerated approval pathway is clearly intended to address lingering controversies that have plagued aducanumab in the months leading up to the FDA’s ruling.

In early-stage trials, there were promising signs that aducanumab might slow cognitive decline, a major Alzheimer’s symptom. In a 2016 trial published in the journal Nature, 125 patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s who received monthly infusions of the drug saw levels of plaques decrease, as did symptoms of cognitive decline.

The decline of the plaques in the brain were “robust and unquestionable” as one Lancet Neurology paper puts it, but the clinical findings were more modest – it wasn’t clear exactly how much people’s cognitive ability benefitted from the treatment.

These early trials eventually led the FDA to allow the drug to skip phase 2 clinical trials, which are designed to identify dosages of the drug, and proceed directly to phase 3 clinical trials. This move was criticized by some physicians.

Those phase 3 clinical trials, called ENGAGE and EMERGE, have become the center of tension. Both trials tested monthly intravenous injections of the drug on about 1600 patients with early Alzheimer’s. In 2019, both trials were halted because the drug didn’t appear to be slowing cognitive decline, the primary endpoint of the trials.

Additional data analyzed in late 2019 from the EMERGE trial suggested that the drug was linked with a 23 percent less cognitive decline, compared to a placebo. There were side effects: namely swelling and inflammation of the brain. This was seen in about 40 percent of Phase 3 trial participants, though most were symptomatic and most of those with symptoms (headache, nausea, visual disturbances) resolved after 4-16 weeks.

Still, even the new data wasn’t enough to convince an independent FDA advisory committee, who, in November 2020 did not endorse approval of the drug.

On Monday, The FDA, argued that the drug’s effects on beta-amyloid plaques were strong enough to suggest that benefit outweighed the risk. Critically, the FDA did not comment on the strength of clinical outcomes – in short, the agency is basing this approval on the drug’s ability to address beta-amyloid plaques, not how well each patient cognitive function responds to the drug. The followup study will need to address that outcome directly.

Still, about 6 million people have Alzheimer’s in the US, and patient organizations have rallied in response to this drug. The Alzheimer’s Association has hailed the drug as a “victory for people living with Alzheimer’s.”

Ahead of the FDA’s decision on Monday, it was clear that, should aducanumab be approved, it would soon become a “blockbuster drug.” The financial picture around the drug seems to support that idea.

Trading of Biogen shares were initially halted, but have since jumped 40 percent today, following the announcement. Shares of Eisai Co. Ltd, a Japanese company working with Biogen jumped over 46 percent in the first three hours following the FDA’s approval.

Certainly, Biogen was banking on this approval as a long-term strategy. In an April 2021, earnings presentation, the company estimated that there were 600 sites ready to launch the treatment post-approval. Biogen has also submitted marketing authorization applications for aducanumab in Brazil, Canada, Switzerland and Australia. On June 7, the company announced that a year’s supply of the drug would cost $56,000.

In the wider world of Alzheimer’s drugs, it’s possible other companies may see this approval as proof-of-concept for other drugs targeting beta amyloid plaques.

In an editorial that accompanied the 2016 Nature paper on aducanumab, Eric Reiman, executive director of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, argued that scientific confirmation that beta-amyloid-targeted treatment slows cognitive decline would be a “game changer.” The aducanumab trials have been likened to a test of this idea. Speaking to The Financial Times, Howard Filit, founding executive director of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, called aducanumab “the first rigorous test of the beta-amyloid hypothesis.”

In that sense, conditional approval may indicate that the FDA is sympathetic to this form of Alzheimer’s treatment.

There’s at least one more beta-amyloid targeted drug from a major drugmaker (Eli Lilly) clinical trials. We may see some more of them emerge soon, provided that Biogen’s confirmatory study of aducanumab doesn’t prompt the FDA to withdraw approval.