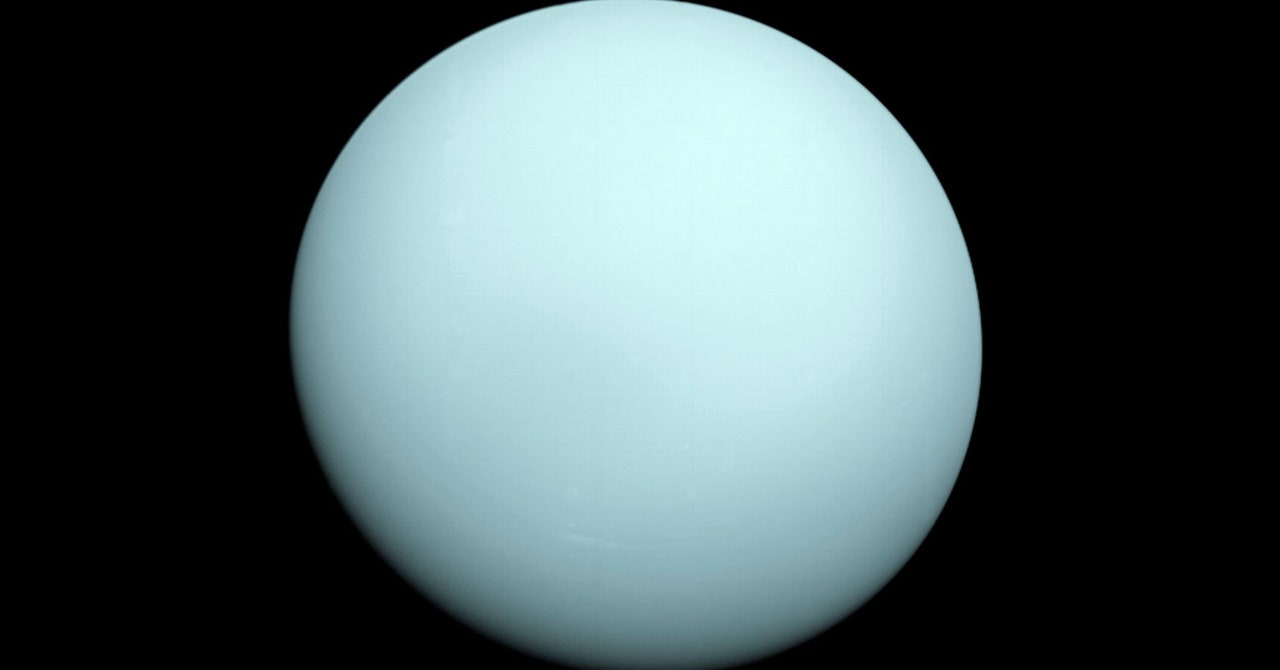

For the past couple of decades, NASA has been investing in spacecraft to conduct up-close examinations of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Now it’ll likely be Uranus’ turn.

On Tuesday, a team of planetary science and astrobiology researchers released a detailed new report called a decadal survey, which lays out research priorities for their field. Like the census, a decadal survey comes out every 10 years and has important political implications. The previous assessment by planetary scientists prioritized a Mars sample return mission and a probe to Jupiter’s moon Europa—the federal government agreed to fund those in the 2020s. This time, the researchers argue that a Uranus orbiter and probe should be considered “the highest-priority new flagship mission” that could be developed and even launched within the next decade. Their second-place choice is to search for life on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, which harbors an underground ocean, a tiny bit of which sprays out in plumes.

These new recommendations could eventually become realities too. That’s because the report, organized by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, has broad support. It’s respected by members of Congress, NASA, and the scientific community. “It’s very likely to me that the Uranus orbiter will happen. This kicks off an interesting process of morphing ideas and words into metal and technology of spacecraft that takes decades,” says Casey Dreier, the senior space policy adviser for the Planetary Society, a nonprofit research organization based in Pasadena, California, whose president served on the report’s steering committee. “We’ll be enjoying Uranus jokes for years,” he adds.

The report calls for a spacecraft that would study the ice giant’s interior and atmosphere, its magnetic field, its rings, and its many moons. If NASA has the funding and support to get started within the next couple of years, the authors write, such a probe could be launched by 2032 and swing by Jupiter for a gravity-assisted boost in speed that could help it arrive at the end of that decade. But considering the major pieces of the NASA budget pie now focused on Mars and Europa, launching such a spacecraft later in the 2030s might be more likely, Dreier says. Then the voyage itself would take the better part of a decade.

A few decades ago, Mars and Venus seemed like the obvious places to look for extraterrestrial life, since those planets might have once held liquid water on the surface, which all known life-forms need. But there may be other life-friendly spots in our neighborhood too: ocean worlds, which in our solar system are distant moons with liquid lakes or oceans, some deep underground.

The new report, titled “Origins, Worlds, and Life,” emphasizes such worlds, since they might host the alien microbes that scientists have long been hunting for. Known ocean worlds include Europa and Titan, moons of Jupiter and Saturn that NASA’s targeting with the Europa Clipper and Titan Dragonfly missions. But Enceladus, a smaller brother of Titan’s, is an ocean world in its own right, and researchers picked it as the second priority, a place to send an “orbilander,” a spacecraft that will function as both an orbiter and a lander. “It’s been Enceladus’ turn for so long. It’s been begging for us to come,” says Nathalie Cabrol, an astrobiologist and head of the Carl Sagan Center for Research at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California, an organization focused on the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.