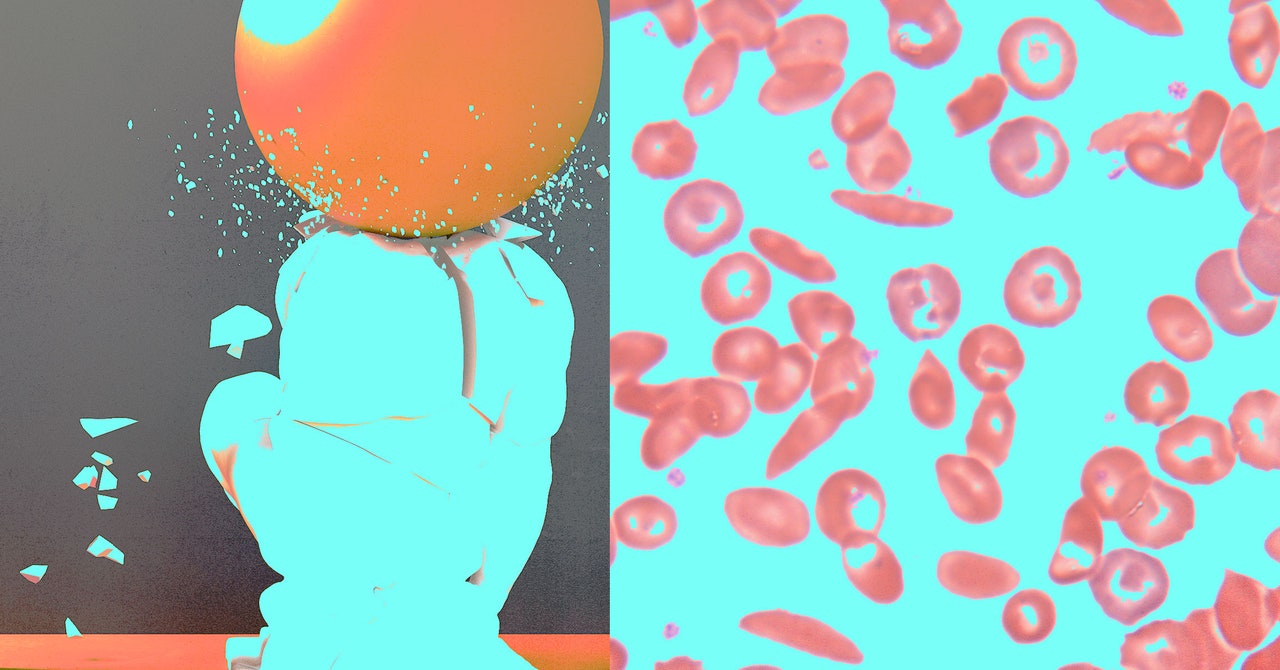

Evie Junior’s life has been defined by pain. He was born with sickle cell disease, which causes red blood cells to be sticky and C-shaped, not smooth and round. These cells are supposed to move freely through blood vessels, carrying oxygen to the body. But in people with this inherited form of anemia, they clump together and block blood flow. This triggers excruciating episodes known as pain crises, which can happen anywhere in the body and last for hours or even weeks. The disease damages organs over time and can cause strokes and early death.

People with sickle cell are often fatigued because their red blood cells die fast, cutting off oxygen to the body. Strenuous exercise, sudden temperature changes, and dehydration can also trigger a pain crisis. Growing up in the Bronx, in New York City, Junior recalls getting winded easily and having to be careful when playing sports or swimming. The pain was so bad that he often missed school.

As an adult, it didn’t get easier. Sometimes he could ward off the pain with ibuprofen and get back to work the next day. But every few months, a severe crisis sent him to the hospital. Things got so bad that in 2019, he enrolled in a clinical trial at the University of California, Los Angeles, which has been testing a gene therapy to cure sickle cell. It involves genetically modifying patients’ blood-forming stem cells in the lab so that they can produce healthy red blood cells. The procedure is experimental. Junior knew there was a chance it wouldn’t work. “I felt like it was time for a Hail Mary,” he says. “My entire life up until that point was being sick.”

In July 2020, he received a one-time infusion of his own altered stem cells. Three months after the treatment, tests showed that 70 percent of his blood cells had the intended change—far above the threshold needed to eliminate symptoms. He hasn’t had a pain crisis since. He can do more outdoor activities, and he doesn’t have to worry about missing work. He plans to go skydiving soon—something he never would have dreamed of doing before. “My quality of life is so much better now,” he says.

Junior, who’s now 30 years old, is one of dozens of sickle cell patients in the US and Europe who have received gene therapies in clinical trials—some led by universities, others by biotech companies. Two such therapies, one from Bluebird Bio and the other from Crispr Therapeutics and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, are the closest to coming to market. The companies are now seeking regulatory approval in the US and Europe. If successful, more patients could soon benefit from these therapies, although access and affordability could limit who gets them.

“I’m optimistic that this will be a game-changer for these patients,” says Cheryl Mensah, a hematologist at Weill Cornell Medicine and New York-Presbyterian Hospital, who treats adults with sickle cell disease. “If more patients undergo curative therapies, especially at younger ages, there will be fewer adults who have chronic pain and fatigue.”

Sickle cell disease affects around 100,000 people in the US, and millions around the world. The vast majority are of African ancestry, but the disease also affects Hispanic people from Central and South America and those of Middle Eastern, Asian, Indian, and Mediterranean descent.