With any organ transplant, doctors are trying to balance how to prevent infections while tamping down the immune system. Without immunosuppressive drugs, the transplant organ will be rejected. But giving patients too much of these drugs makes them susceptible to infections.

That’s what researchers think happened in Bennett’s case. To treat the CMV infection, doctors gave Bennett a therapy called intravenous immunoglobulin, which is meant for patients with compromised immune systems, including transplant patients. A concentrated pool of antibodies from thousands of human donors, the treatment likely contained natural antibodies that attacked the pig organ and damaged muscle cells.

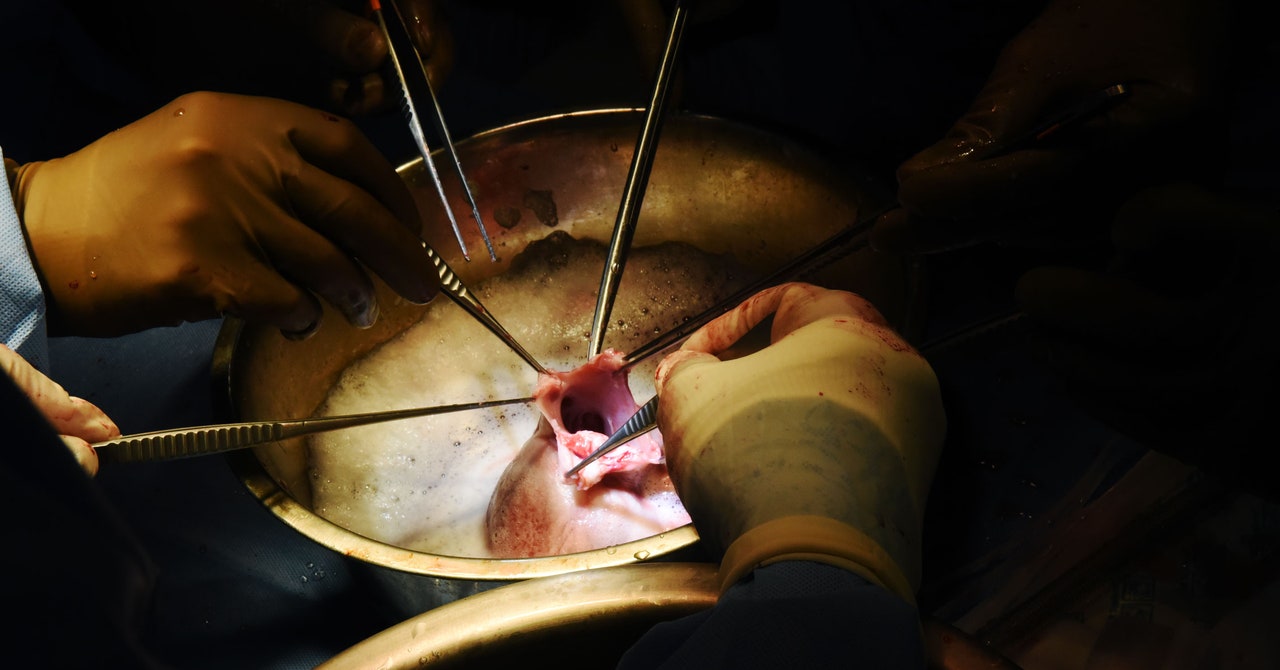

The Maryland doctors are taking different steps to prevent Faucette’s new heart from being rejected. For one, they told WIRED in December that they had developed a new, more sensitive test to detect very small amounts of pig virus DNA. Before the latest transplant, they tested the donor pig regularly for CMV and other porcine viruses, as well as bacteria and parasites. “At the present time, we have no reason to believe this donor pig is infected with porcine PCMV, which is the virus that was identified in our first xenotransplant recipient,” a university spokesperson told WIRED in an email.

Doctors are treating Faucette with traditional immunosuppressive drugs, along with an investigational antibody therapy called tegoprubart, developed by California biotech company Eledon Pharmaceuticals. The drug works by blocking CD154, a protein involved in immune rejection, and is given via IV every three weeks. As with other immunosuppressive drugs, Faucette must receive it for the rest of his life to prevent his new heart from being rejected. “When you block this receptor, it’s very, very effective to prevent transplant rejection,” says Steve Perrin, Eledon’s president and chief scientific officer.

When the Maryland surgeons performed Bennett’s transplant in January 2022, they didn’t have access to Eledon’s drug because it had not yet been tested in humans. Now, more than 100 people have received the drug in early clinical trials. Tegoprubart has also been tested in non-human primates and been shown to increase the life of transplanted pig organs in those animals.

The next few weeks will be crucial to determine whether the transplanted pig heart will continue to function normally. “I’m hopeful that this will be the correct regimen for the patient and that he will be able to live a long life with the xenograft,” says Jayme Locke, an abdominal transplant surgeon at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who wasn’t involved in the heart cases. In August, Locke’s team published a study showing that a genetically modified pig kidney functioned normally in a brain-dead patient for a week.

In a separate xenotransplant experiment, a team at NYU Langone announced earlier this month that it kept a pig kidney working for two months in a brain-dead person.

The US Food and Drug Administration granted emergency approval for Faucette’s surgery earlier this month through its “compassionate use” pathway. This process, which was also used for Bennett’s transplant, is applied when an unapproved medical product—in this case, the genetically modified pig heart—is the only option for a patient with a serious or life-threatening condition.

Pierson thinks these individual cases of pig-to-human transplants will help generate evidence needed for more formal clinical trials that will include multiple patients. He is optimistic that a pig heart will function longer in this second patient. “Full stop,” he says. “It may not work every time we do it, but we’re going to learn a lot from these one-offs.”