For its part, India next plans to partner with Japan on the Lunar Polar Exploration rover, or Lupex, which could launch as early as 2026 and will examine water deposits near the south pole.

The US and China have been active on and around the moon for years. NASA and its international and commercial partners have already launched the first mission of the Artemis program. The uncrewed Artemis 1 orbited the moon in late 2022, and NASA plans to send astronauts into lunar orbit in 2024. In 2026, it plans to send people to the moon’s surface for the first time since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. Ultimately, the US is gearing up for a permanent presence on the moon, including a moon base and the Lunar Gateway space station.

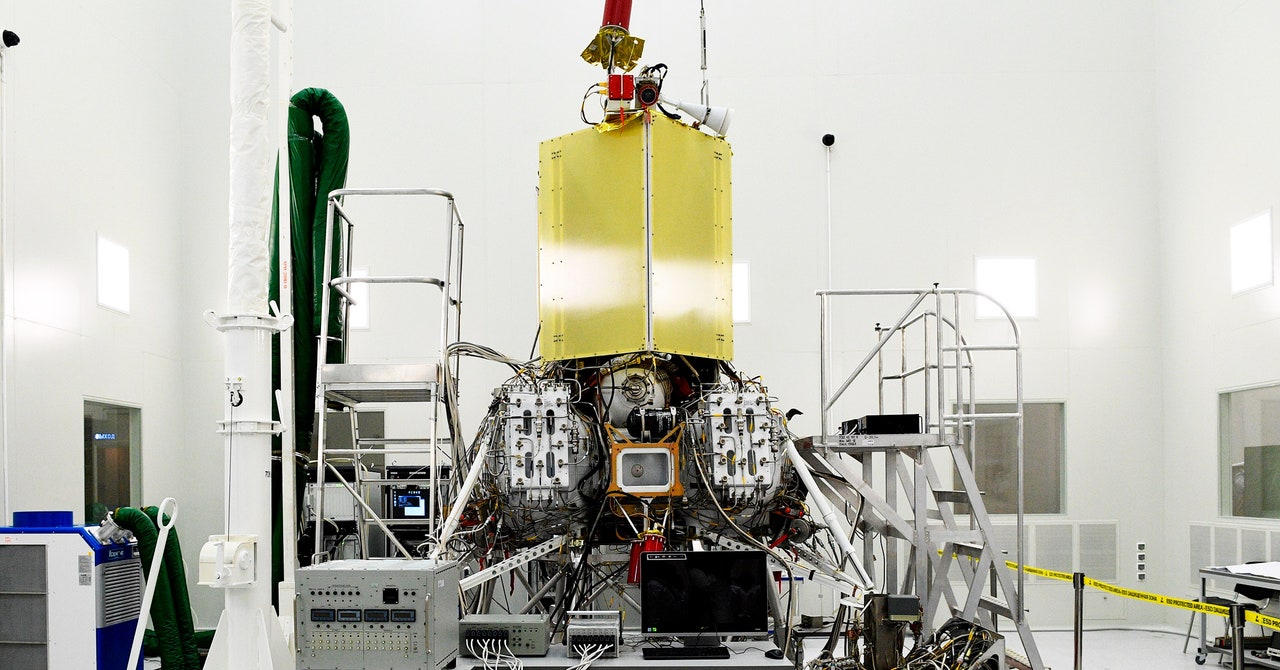

NASA has also invested in commercial entities, such as Astrobotic’s Griffin lander that would deliver the space agency’s Viper rover near the south pole in late 2024. (Astrobotic plans to attempt landing a smaller spacecraft in late 2023 on the inaugural flight of the United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket.) The US has also developed the Artemis Accords, guidelines for moon exploration and using lunar resources.

China has taken its own path with its ambitious Chang’e program. That began with a lunar orbiter in 2007 and was followed by other orbiters, a lander, and then a rover in 2019. Chang’e 5 successfully sent moon samples back to Earth in 2020. China plans Chang’e 6, another sample-return mission, for 2024, followed by the Chang’e 7 rover in 2026. Like the US, China plans to have a permanent presence on the moon with its International Lunar Research Station at the moon’s south pole, planned for construction in the 2030s.

The fact that the US and China have dominated lunar exploration over the past decade isn’t for lack of trying by others. Recent landing attempts have failed, including Japan’s Ispace lander in April and Israel’s Beresheet lander in 2019, which infamously included a payload of hardy tardigrades, or “water bears.” India’s Chandrayaan-2 lander also crashed on the moon later that year.

There’s a reason why countries want to reach key lunar sites first. While no one can own territory on the moon, according to the Outer Space Treaty, the Artemis Accords offer what some might describe as a loophole: safety zones. If someone sets up a landing pad, equipment, or infrastructure, others are expected to keep their distance from that spot in the interest of safety. This could let a country or even a company effectively claim crucial real estate, Steer says.

And earthly geopolitics are inevitably at play. It matters who lands first, and who collaborates with whom. For example, China has invited Russia to partner on its lunar research station, along with Venezuela, the United Arab Emirates, and Pakistan. India sometimes partners with the US; in June, during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the White House, India became the 27th country to join the Artemis Accords.

For now, India and Russia are both positioned to take big strides in the next leg of the space race. Next week will reveal if anyone pulls ahead.