If you memorized the periodic table, if you whipped up exothermic reactions in your kitchen, Wenting Zhu and Yan Liang are here to renew your relationship with the elements.

To generate the images in their 300-photo collection The Beauty of Chemistry, out today, Zhu and Liang utilized infrared thermal imaging techniques, along with high-speed and time-lapse micro photography to plunge readers into the minute world of molecules and the often stunning reactions between them. With atomic clarity, science writer Philip Ball narrates this visual tour through the under-appreciated chemical beauty that surrounds us, from describing the principles that generate the unique symmetry of a snowflake to connecting the lifelike tendrils created by silicate salts to the origins of life itself.

Perhaps the most basic—and astonishing— of these concepts is the hydrogen bond, which holds together the literal stuff of life: water. Each water molecule is comprised of two hydrogen atoms bonded to an oxygen atom, but oxygen has six electrons in its outer shell. Only two electrons are needed to form that chemical bond with hydrogen, so four negatively charged electrons, grouped by twos in “dangling” pairs, are hovering out there in micro-space hoping for a way to balance themselves out. These pairs pull weakly on the hydrogen atoms bonded to neighboring water molecules, forming brief, one-trillionth-of-a-second bonds before breaking and reforming with another hydrogen atom. And it’s this constant, unceasing dance that allows for the chemical motion that makes life possible, what Ball calls a “molecular dialog” that hovers between order and chaos.

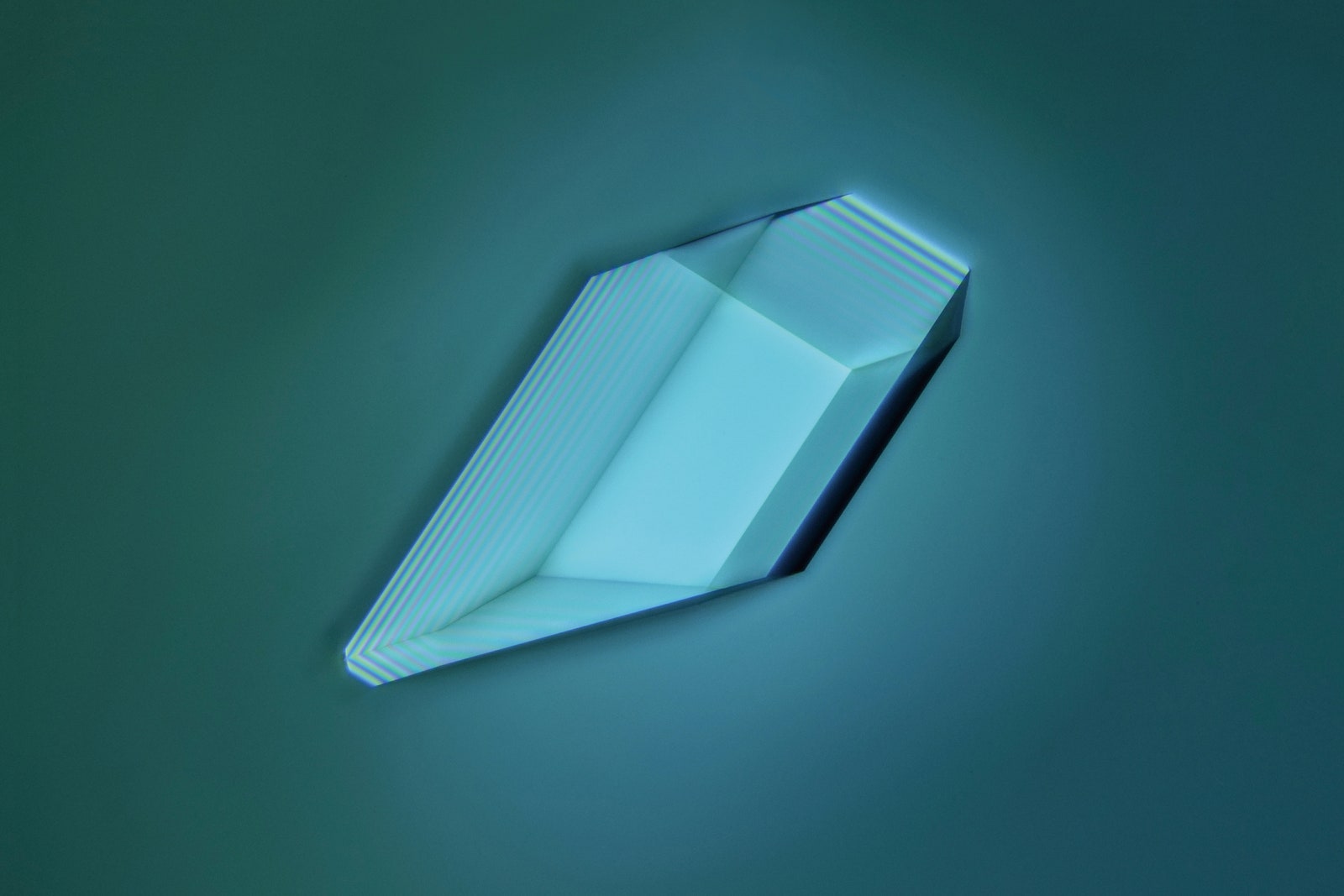

Chromium(III) hydroxide

Photograph: Wenting Zhu and Yan Liang

This chromium hydroxide precipitate is in the process of solidifying as it swirls and dilutes within its container. This reaction occurs when two liquid compounds, containing both positively and negatively charged ions, come together and perform a molecular reel, in which they trade partners. In this case, chromium chloride and sodium hydroxide swap ions. The positively charged chromium and negatively charged hydroxide molecules are attracted to one another because they balance out energetically. They form tight bonds that freeze the molecules into place, creating a solid byproduct that doesn’t have room for all those water molecules to fit neatly. The reaction also creates sodium chloride, commonly known as table salt, which dissolves in water just fine.

Copper sulfate crystal

Photograph: Wenting Zhu and Yan Liang