As autumn faded to winter last year, a few infectious disease researchers started turning their attention away from the Covid-19 pandemic and back to something more familiar. This was the time of year they’d ordinarily start looking at their numbers for influenza, the seasonal flu—to see how bad the outbreak would be, and to assess how well that year’s vaccine dealt with the protean respiratory virus.

The answer was: bupkis. Hardly anyone was sick or dying from the flu. A year earlier, during the 2019–20 flu season—basically fall and winter, peaking in December, January, and February—18 million people in the US saw a doctor for their symptoms, and 400,000 had to be hospitalized. Overall, 32,000 people died. But in the current season, cases barely crossed four digits. “There’s always vaccine season and flu season. We’re used to working in that pattern, and the pattern is gone,” says Emily Martin, an epidemiologist at the University of Michigan School of Public Health who’s part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s flu-monitoring network. “Now, I’m glad I didn’t have to do Covid control and influenza control at the same time. That would have been a disaster. But at the same time, it is this strange year.”

Strange indeed. And it’s not just the flu. Case numbers for respiratory syncytial virus, which primarily affects babies and, like influenza, has a seasonal rhythm, also bottomed out. According to a paper that came out last week, the missing-in-action list also includes enterovirus D68, a likely culprit behind the polio-like kids’ disease acute flaccid myelitis. The virus and AFM come and go on a roughly every-other-year cycle, and the last round in North America was in 2018. In 2020, they, too, missed their cue.

The why of it isn’t really a mystery. Probably. Most likely, all the mask wearing, physical distancing, handwashing, and other “non-pharmaceutical interventions” that everyone—OK, almost everyone—did to prevent the spread of Covid-19 also put the kibosh on those other viruses. That’s not the only hypothesis going, but it’s a good one.

The mystery is the how and the what-next. The answers might teach scientists more about how those other diseases infect people, and about how to stop them. The mechanics of why those NPIs crushed at least three other respiratory viruses while Covid-19 ran rampant aren’t clear. And even less clear is what a Year Without a Flu will mean for next winter, and for winters after that. Influenza kills anywhere from 12,000 to 61,000 people in the US every year and costs the economy $11 billion annually, according to one estimate. For decades, centuries even, people have just sort of accepted that risk. But if it turns out it’s almost entirely preventable, will people’s willingness to tolerate the risk change too?

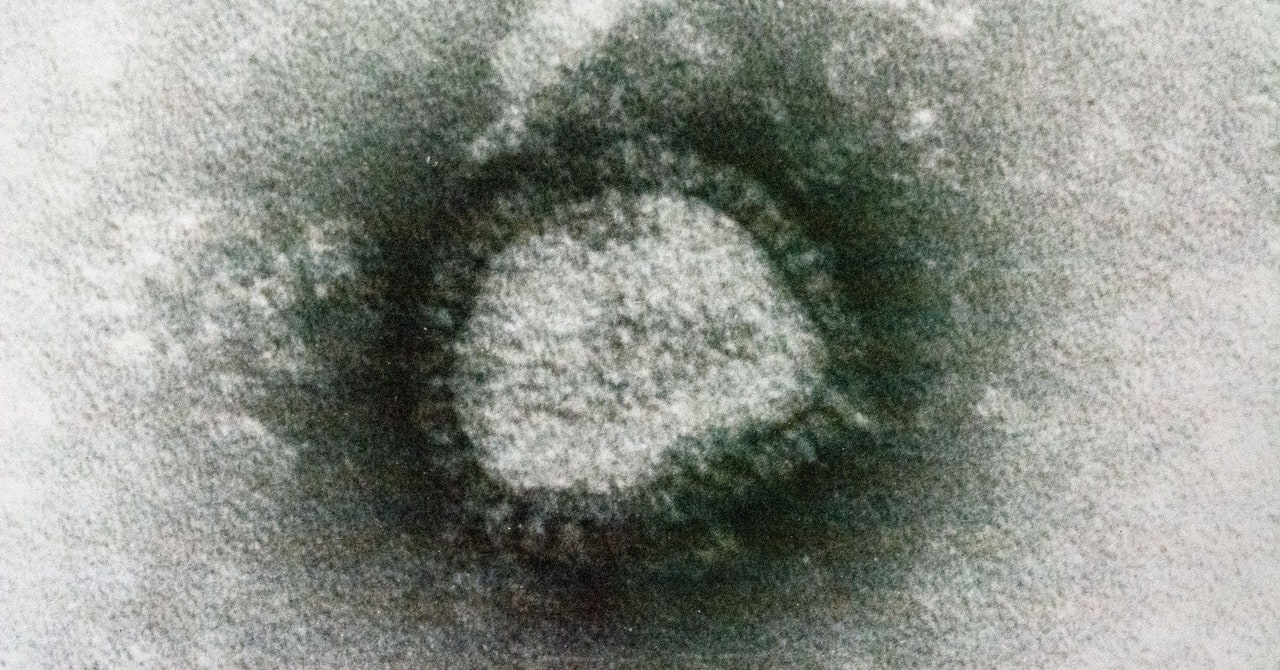

Pandemics happen when a virus hits its evolutionary groove. The virus that causes Covid-19 is called SARS-CoV-2, and when it dropped in late 2019, no human immune system had ever seen it before. Nobody had any defenses. The fact that people who didn’t have any symptoms could transmit it made it different from most of its respiratory-pathogen cousins—just different enough to take advantage of human social interactions and go global.

But just as it takes only the smallest circumstance or genetic twist to turn a virus into a pandemic, the disease version of an arena-filling band, it doesn’t take much to limit a disease to the equivalent of playing small clubs, either. “The Covid-19 control measures—mask wearing and social distancing—really work, and they work really well for other respiratory pathogens too,” says Rachel Baker, an epidemiologist at Princeton University. The key difference is probably that those other diseases have been playing gigs for thousands of years, and humans are a little bit inured to their charms. Even the flu, with its famously mutable genome that requires a new vaccine every year, leaves behind some level of population-scale immunity. “With the seasonal diseases, we have a lot of population immunity, we have vaccines, and most people over 2 years old have had RSV,” Baker says. “That’s why you don’t have a seasonal pandemic.”