We’re bathing in an uncertain universe. Astrophysicists generally accept that about 85 percent of all mass in the universe comes from exotic, still-hypothetical particles called dark matter. Our Milky Way galaxy, which appears as a bright flat disk, lives in a humongous sphere of the stuff—a halo, which gets especially dense toward the center. But dark matter’s very nature dictates that it’s elusive. It doesn’t interact with electromagnetic forces like light, and any potential clashes with matter are rare and hard to spot.

Physicists shrug off those odds. They’ve designed detectors on Earth made out of silicon chips, or liquid argon baths, to capture those interactions directly. They’ve looked at how dark matter may affect neutron stars. And they’re searching for it as it floats by other celestial bodies. “We know we have stars and planets, and they’re just peppered throughout the halo,” says Rebecca Leane, an astroparticle physicist with SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. “Just moving through the halo, they can interact with the dark matter.”

For that reason, Leane is suggesting that we look for them in the Milky Way’s vast collection of exoplanets, or those outside our solar system. Specifically, she thinks we should be using large sets of gas giants, planets like our own Jupiter. Dark matter can get stuck in planets’ gravities, as if in quicksand. When that happens, particles can collide and annihilate, releasing heat. That heat can accumulate to make the planet piping hot—especially those near a galaxy’s dense center. In April, Leane and her coauthor, Juri Smirnov from Ohio State University, published a paper in Physical Review Letters which proposed that measuring an array of exoplanet temperatures toward the Milky Way’s center could reveal this telltale trace of dark matter: unexpected heat.

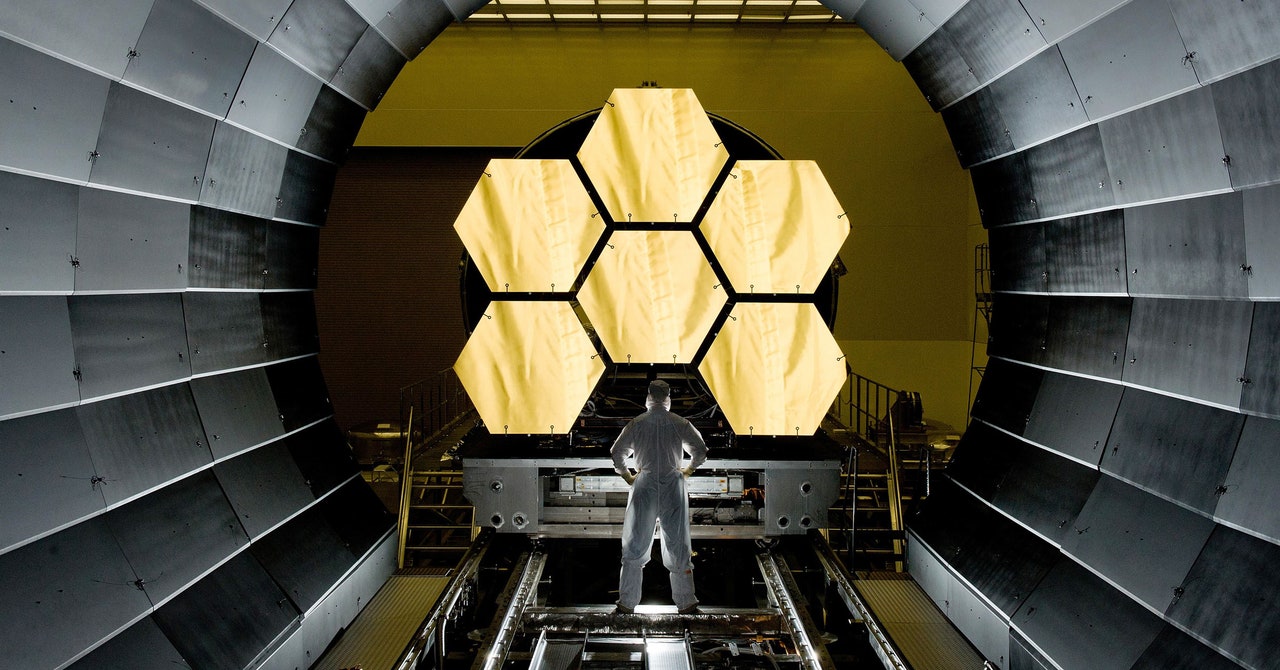

Their paper was based on calculations, not observations. But the temperature spikes Leane and Smirnov predict are noticeably large, and we’ll soon have a cutting-edge thermometer: NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope is expected to launch this fall. The JWST is an infrared telescope, and the most powerful space telescope ever built.

“It’s a very surprising and inventive approach to detecting dark matter,” says Joseph Bramante, a particle physicist with Queen’s University and the McDonald Institute in Ontario, who was not part of the study. Bramante has previously studied the possibility of detecting dark matter on planets. He says that detecting unusually hot planets pointing toward the Milky Way’s center “would be a very compelling smoking gun signature of dark matter.”

It’s been less than 30 years since astronomers detected the first exoplanets. Because they’re much dimmer than the stars they orbit, they are hard to see on their own; they usually reveal themselves by just barely obscuring the light from those stars. Astronomers also find and size up exoplanets with tricks like micro-lensing. (One star’s gravity warps our view of a further star’s light, and a planet between the two creates a blip in that effect.) The exoplanet tally now sits at 4,375, but some 300 billion could be out there.

Dark matter usually moves freely among these islands of “normal” matter, meaning that it slides past objects without interacting. But when one dark matter particle happens to nudge ordinary particles like protons, it slows down by a smidgeon. “Just like billiard balls,” Leane says. “It just comes in, literally hits it, and then bounces off. But it can bounce off with less energy.”

Accumulating enough of these collisions slows them too much to escape a planet’s gravity. Physicists expect that when this “scattering” and capture happens, dark matter particles can collide and annihilate each other. The once-energetic dark matter decays into other particles—and heat. “When they smash together,” Leane says, “it puts energy into the planets.”