Eight people who work for the New York Yankees baseball team, including a player, have tested positive for Covid-19—and all of them were vaccinated against the virus a little more than a month ago.

That seems bad. But don’t panic. (Or, if you’re a Red Sox fan, stop smiling.) These “breakthrough” cases don’t mean that vaccines don’t work, or that some vicious new vaccine-proof variant went on a superspreading streak through the Yankees’ locker room. They do mean, though, that it might be a little early to take off those masks.

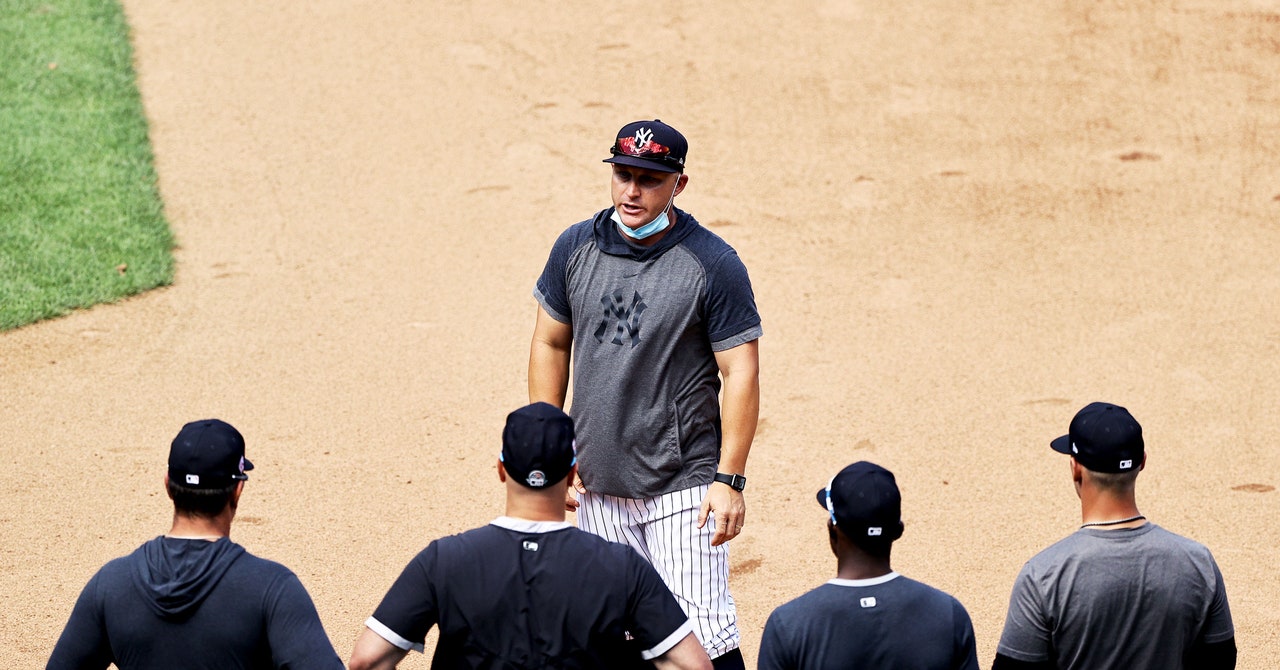

Manager Aaron Boone announced seven cases among team staff to the press on Wednesday; on Thursday the Yankees also put shortstop Gleyber Torres on the Covid-19 injured list—he had the disease in December, got vaccinated, and has tested positive again. Six of the seven staff cases were, thankfully, asymptomatic. The reason anybody found out about them was that the team regularly tests the staff and players.

That’s the curve ball here. “Breakthrough cases are underreported, since many will be asymptomatic,” says Ana Isabel Bento, a disease ecologist at the Indiana University School of Public Health. “And most people won’t get tested unless required to, or they’re experiencing symptoms.”

So it’s impossible to tell how weird this team outbreak really is, because nobody knows the denominator—the number of people who, after getting vaccinated, still get infected but never get sick. The Yankees got the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine on April 7. That’s enough time for their immune systems to get completely spun up against the virus. But no vaccine is perfect. “Johnson & Johnson’s was 100 percent effective at preventing hospitalization and death, 85 percent effective against severe cases, and 72 percent effective at preventing moderate illness in various trials,” Bento says. “So we expected that if vaccinated individuals become infected, they will most likely be asymptomatic.”

In the interest of beating the raging pandemic, most of the Covid vaccines got tested against their ability to prevent severe illness and death. They all do that very well. “But to figure out if this outbreak is consistent with reported vaccine efficacy, which J&J did report against infection, you’d want to compare the rates,” says Sarah Cobey, an epidemiologist and evolutionary biologist at the University of Chicago.

Which we can do, almost. In trials of the vaccine, Johnson & Johnson researchers actually tested some subjects for asymptomatic infection: Did people in the trial who tested negative for the virus before the study then test positive for antibodies against the virus after, whether they got sick or not? About two and a half months after vaccination, 2.8 percent of the people who didn’t get the vaccine were sick without symptoms. But so were 0.7 percent of people who did get vaccinated. That’s an efficacy, a reduction in relative risk, of about 74.2 percent (with a pretty wide confidence interval, indicating that the statistical power here is only so-so). In a preprint posted earlier this week (so not yet peer reviewed), independent researchers looking at real-world results from the J&J vaccine at two weeks after the shot found that just three of 1,779 vaccinated people tested positive for the virus that causes Covid-19, compared to 128 people out of 17,744 unvaccinated folks. That’s a very, very good rate—but not 100 percent.

The problem is, the Yankees haven’t said how many people overall were vaccinated—a team spokesperson hasn’t responded to my questions—so it’s impossible to tell whether eight breakthrough cases is exceptionally bad or just par for the course (if you’ll pardon a metaphor from a whole other sport).