In 2016, a rape survivor voluntarily provided her DNA to San Francisco law enforcement officers so that her attacker might be brought to justice. Five years later, the sample she provided led police to connect her to an unrelated burglary, according to San Francisco district attorney Chesa Boudin. The woman faced a felony property charge, but Boudin dropped the case, saying the use of her DNA was a violation of her Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures.

The incident could deter survivors of sexual assault from coming forward if they think their DNA could be used to implicate them in a future crime. It also raises legal and ethical questions about the broader law enforcement use of genetic evidence. “We should encourage survivors to come forward—not collect evidence to use against them in the future. This practice treats victims like evidence, not human beings,” Boudin said in a February 14 statement.

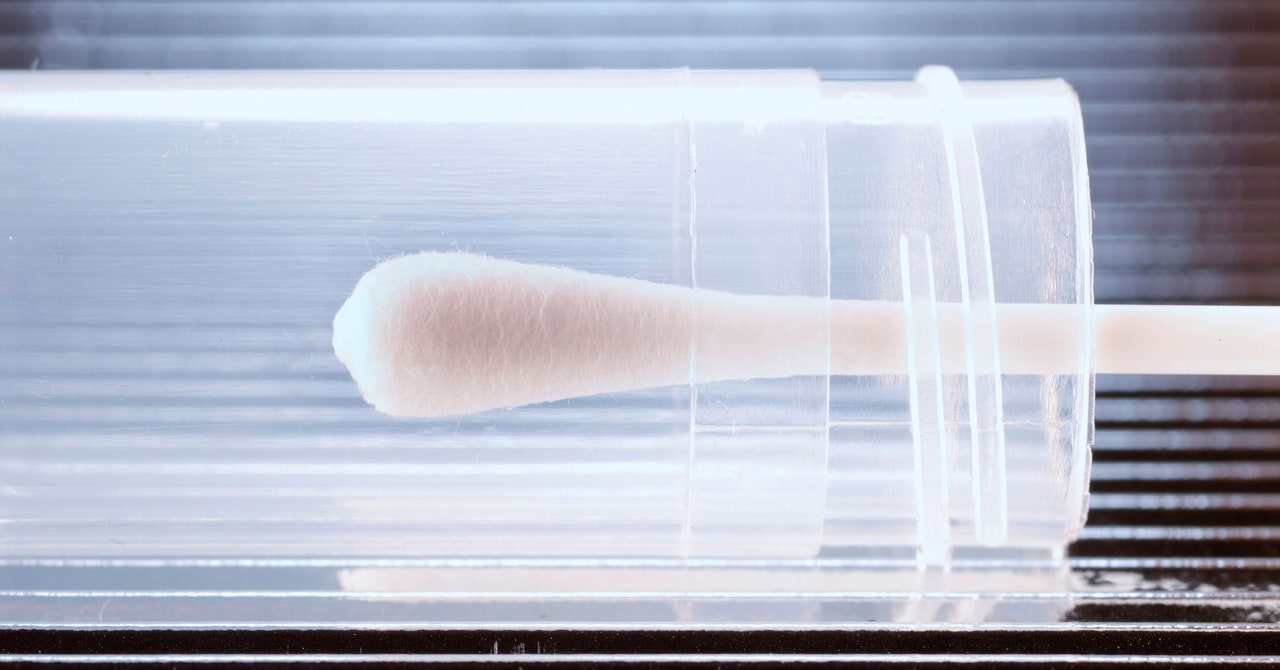

More than 300,000 people were raped or sexually assaulted in 2020, according to the Department of Justice’s 2020 Criminal Victimization Report. Yet less than 23 percent of those assaults were reported to police, down nearly 34 percent from 2019. Many survivors are also reluctant to undergo a forensic exam, also known as a rape kit, out of fear or shame. During the exam, a nurse collects biological evidence that may contain DNA from the assailant, such as blood, hair, saliva, and skin cells. Survivors may also be asked to provide a sample of their own DNA as a reference to determine if genetic material found at the crime scene belongs to them or someone else.

“Sexual assault victims subject themselves to this very invasive exam for one purpose, and that is to identify their assailant,” says Camille Cooper, vice president of public policy at RAINN, the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, a nonprofit that aims to prevent sexual assault and help survivors. “Any use of their DNA for any other purpose is wholly inappropriate and unethical.”

And yet, there’s currently no uniform practice regarding what crime labs do with reference DNA samples after testing. Federal law does prohibit police from uploading victims’ DNA profiles to a national database known as the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, which is maintained by the FBI. CODIS is used to link violent crimes like homicides and sexual assaults to known offenders and has strict rules for what kind of profiles can be submitted. It contains DNA collected from crime scenes, from people arrested for or convicted of felonies, and to a lesser extent, from unidentified remains. People who are released from custody or found not guilty can petition to have their information removed from CODIS.

But some local police departments operate their own DNA databases outside the purview of CODIS. Most states don’t have laws limiting the kinds of DNA samples that can be stored in them. “Police departments around the country have, over time, developed these separate databases that are largely unregulated,” says Andrea Roth, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley who specializes in forensic science and has researched these databases.