Towering 11,000 feet above a million humans, Mount Etna is one of the most thoroughly-monitored volcanoes on Earth. Hundreds of sensors dot its flanks, and for good reason: It’s Europe’s most active volcano, periodically spewing lava and huge plumes of debris that ground planes and generally make life miserable for those living in its shadow.

But now scientists have been spying on Etna with an unlikely new surveillance device: fiber optic cables, like the ones that bring you the internet. Writing last week in the journal Nature Communications, researchers described how they used a technique known as distributed acoustic sensing, or DAS, to pick up seismic signals that conventional sensors missed. This could help improve the early warning system that people in the surrounding parts of Italy rely on. Millions more around the world are also at the mercy of active volcanoes, which create chaos whether they are large or small.

DAS is shaking up (sorry) science in a big way. When the internet was growing in the 1990s, telecoms ended up laying down more fiber optic cable than they needed, since the material itself was cheap compared to the labor required to bury it. That extra cable remains unused, or “dark,” and scientists can rent it out to run DAS experiments. Engineers use it to monitor land deformation, geophysicists use it to study earthquakes, and biologists are even using underwater cables to pick up the vibrations of whale calls.

Fiber optics work by transporting signals from point A to point B as pulses of light. But if the cable is disturbed by, say, an earthquake, a tiny amount of that light gets bounced back to the source. To measure this, scientists use an “interrogator,” which fires a laser through the fibers and analyzes what comes back. Because researchers know the speed of light, they can determine disturbances at various lengths along the cable: Something happening 60 feet away will bounce back light that takes slightly longer to get to the interrogator than something happening at 50 feet.

These measurements are sensitive. For example, in the spring of 2020, during the early days of Covid-19 lockdowns, scientists at Pennsylvania State University used their campus’ buried dark fiber optics to observe as pedestrian and vehicle movement waned and picked up again. They could even tell the source of the aboveground disturbance by the frequency of its vibration: a human footstep is between 1 and 5 hertz, whereas car traffic is 40 to 50 hertz.

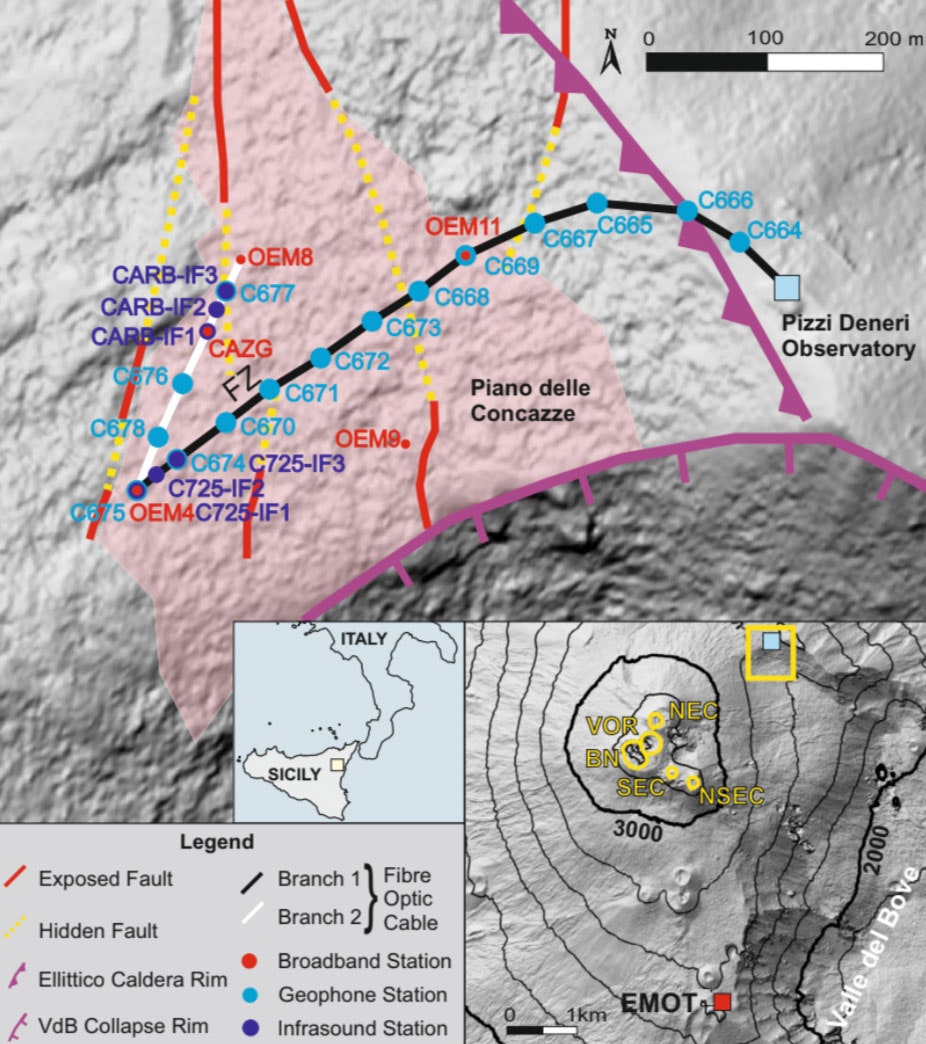

This new research centers on the same idea, only these scientists did it on an active volcano. Because telecoms never bothered to lay fiber optics on Mount Etna, the researchers dug a three-quarter-mile-long ditch less than a foot deep and buried their own, not far from the volcano’s rim.

Illustration: P. Jousset