Haugen says that he and other Kings River representatives tried to negotiate with the would-be attackers. They met around half a dozen times between late 2016 and early 2017. Haugen says they could’ve given a little–they had, after all, been selling that floodwater in deals like the one with Terranova for decades. But, he says, Semitropic wanted a permanent right to the extra water, which the association wasn’t willing to give up for any price.

They ended up on the proverbial courthouse steps, in a battle over whether to crack open the book on the Kings for the first time in decades. In May 2017, three of the Kings River districts filed claims to a million acre-feet of water that they said they already owned—an amount equivalent to more than half the average annual run of the Kings. Sixteen days later, Semitropic filed a petition claiming that the river’s “fully appropriated” status should be revoked or revised, along with an application for rights to 1.6 million acre-feet.

This all sounded to me like very bad news for Don Cameron and his big empty pipes out by Helm—which would very likely stay empty if Semitropic were to win. But he and the rest of the board at the McMullin groundwater agency couldn’t join the coalition condemning Semitropic’s “water grab.” It would have required endorsing the claim that the river had no water to spare. And if that were true, Cameron wouldn’t be the Department of Water Resources’ golden godfather of recharge.

The river users were not happy that McMullin had failed to take their side. They responded with icy hostility. Haugen, the Kings’ watermaster, remains unimpressed by Cameron’s project. “We’ve been doing groundwater recharge in the service area for a century now,” he tells me. “I’ve got plans that can fully put that water to use.” If Terranova wants to help with flood control now and again, that’s fine, he says. “But there are no assurances that there’s ever water for a flood control project,” he continues, offering a grim smile. “Folks want to see our local area sustainable. And there are ways to do it cooperatively.”

But not, apparently, on the Kings. In 2020, Haugen’s association canceled all the river’s floodwater agreements, including the one it had maintained with Terranova for nearly 25 years. Cameron would have to find another way.

On the first floor of a small office building, in the middle of Kerman, California—population about 16,000, one Walmart, one Starbucks—Matt Hurley is drowning in paperwork. He is the general manager of the McMullin Area Ground-water Sustainability Agency and its only full-time staff member. His reception area is cluttered with stacks of large paper maps and plans, and cardboard boxes in various stages of unpack. “I got a few demerits when I was young, and I still need to get a few brownie points to offset those, because I still may be taking the wrong elevator if I’m not careful,” he says. “Hopefully, I can do good on my time left on this planet before I check out.”

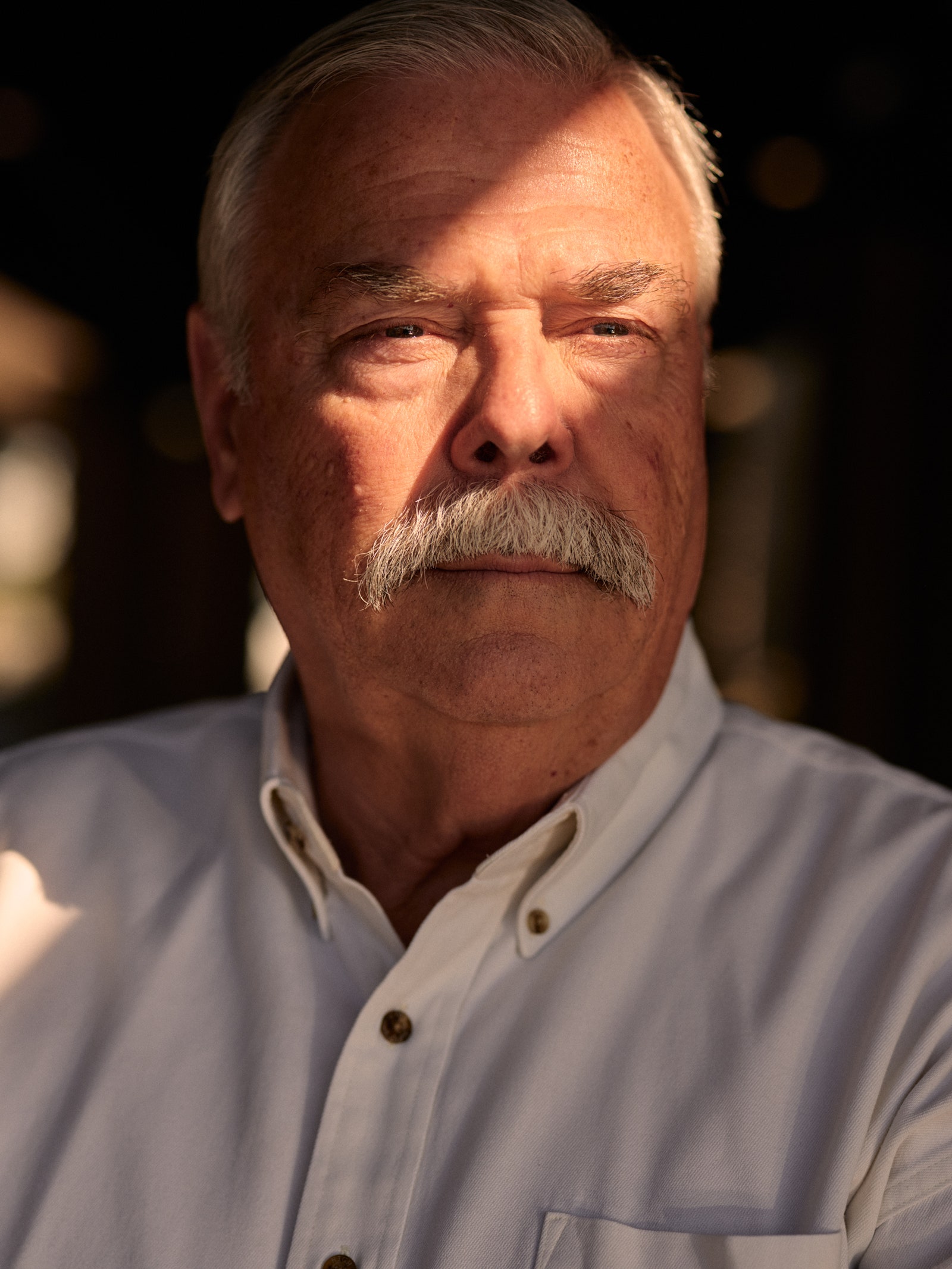

At 68 years old, Hurley is the personification of a strong handshake, tall and booming in a dark blue polo shirt, jeans, and black cowboy boots, with silvery white side-parted hair and a mustache that curls down around the corners. He talks fast and peppers his speech with the folksy self-deprecation of a local agriculturalist (“You’ll figure out I’m wacky as a wooden watch”), which he is not.

Hurley came to McMullin from a water district further south, where John Vidovich owns the majority of property. A 2017 article in The Bakersfield Californian reported that some considered him Vidovich’s “henchman,” obliged to do Sandridge’s bidding. Hurley denied that the relationship was anything more than water district manager and water-wealthy ag king. Now he says that Vidovich is a longtime close family friend and his daughter’s godfather, that Vidovich asked and he provided legal advice on the sale of the $40 million easement to Semitropic, and that, following other asks for other favors, they haven’t spoken since April 6, 2018. Vidovich wanted him to do things that were “gray at best,” Hurley tells me. “He just doesn’t quite get what the whole picture looks like anymore. He’s so driven by making Sandridge bigger and better.”

By the time Hurley got to McMullin, he knew there was extra floodwater on the Kings—and he knew the area’s depleted aquifer could in fact be a huge asset. Unlike other parts of the valley, the McMullin Area hasn’t sunk into the emptied space of its exploited aquifer, making it a natural subterranean water bank. It could store nearly 2 million-acre feet underground, roughly as much as two Pine Flat Lakes.