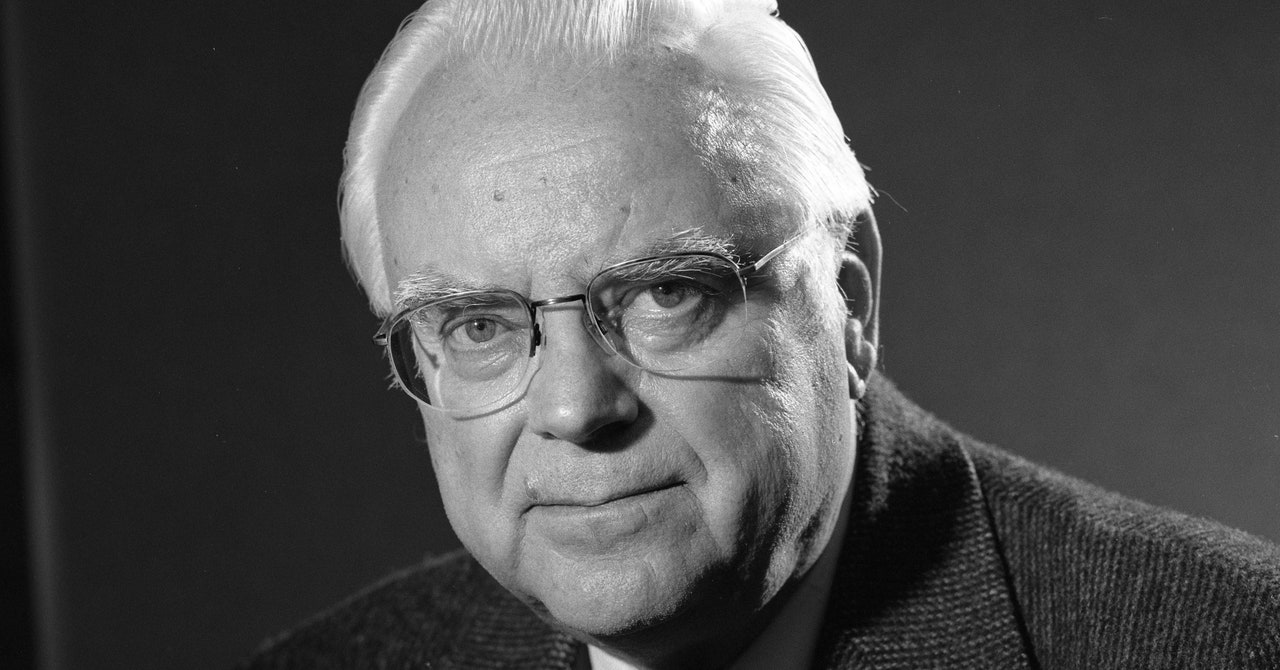

Frank Drake, a leading figure in planetary astronomy and astrobiology who inspired the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI, died Friday, September 2, at the age of 92. “Frank essentially pioneered the field of SETI as a scientific endeavor by being the first to actually conduct a SETI experiment,” says Bill Diamond, president of the nonprofit SETI Institute in Mountain View, California.

Drake was born in Chicago in 1930. He studied engineering physics at Cornell University and then served as an electronics officer on a Navy cruiser for three years. Afterward, he earned his PhD in astronomy at Harvard.

His SETI quest began in 1960, when he was working for the National Radio Astronomy Observatory at its telescopes in Green Bank, West Virginia. Unbeknownst to him, in 1959 a pair of physicists had published a research paper speculating about how far radio signals sent by extraterrestrial civilizations might travel and still be detectable by a receiver on Earth. “It turns out the distance is light-years,” says Seth Shostak, senior astronomer for the SETI Institute, a nonprofit research organization focused on the origins of, and the search for, alien life. “Maybe the sky is filled with signals, but we’ve just never looked for them.”

Drake had already begun leading an effort to do just that. In 1960, he secured approval from the NRAO for Project Ozma (named after the princess in The Wizard of Oz), the first attempt to systematically hunt for alien signals. For a few hours every day, he pointed the facility’s 85-foot radio telescope at Tau Ceti and a handful of other nearby star systems, searching for bumps or wiggles above the background noise that might be signs of an intentional broadcast. He tuned in to a particular range of frequencies, notably one near the 21-centimeter emission line of hydrogen. This is normally a quiet part of the radio spectrum—most worlds would have few emissions in that range—so one could use it as a natural “hailing frequency.” But aside from one false alarm that was probably due to an aircraft, he and his colleagues heard only static.

Although the Green Bank experiment didn’t spot any alien messages, it showed how one could look for them, so the National Academy of Sciences approached Drake to help organize a conference about SETI there. That pivotal 1961 meeting brought together an influential and eclectic group of scientists, including the chemist Melvin Calvin (who was notified of his Nobel Prize win at the meeting), a dolphin intelligence researcher, the authors of the 1959 paper, and a young Carl Sagan, who would become a frequent collaborator with Drake.

At that conference, Drake began developing a seminal formula that later became known as the Drake Equation. Still in frequent use in various forms today, that formula tries to reach a ballpark figure for the number of alien societies that could exist within our galaxy and that might be trying to message us. Its variables include the birth rate of stars, the abundance of planets orbiting them, the fraction of those that are habitable rocky worlds, the portion of those on which life could develop, the fraction of alien civilizations that might transmit signals that can be detected, and the estimated lifetime of those civilizations.

While the variables about stars and planets can be constrained with some precision, no one really knows how long intelligent civilizations typically last. (After all, we have only earthling civilizations to extrapolate from. Although some have flourished for millennia, humans are just babies, cosmically speaking—and they’ve already threatened their very existence with nuclear war and climate change and still don’t know how to deflect killer asteroids.) “Most of the important terms of the equation are unknown. You could say, ‘The equation is useless,’ but that’s not true, because it is a good way to organize your ignorance,” Shostak says. It shows that questions about intelligent life and our efforts to listen for it need to bring together other fields, too, including astrophysics, geology, biology, and sociology.