The Aedes aegypti mosquito is not just a nuisance—it’s a known carrier of dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, and Zika viruses. Distinguished by the black and white stripes on its legs, the species is one of the most dangerous to humans.

In the Brazilian city of Indaiatuba, an effort is underway to eliminate these pests before they have a chance to spread illness. The weapon: more Aedes aegypti mosquitoes—but ones genetically engineered to kill their own kind. Made by British biotechnology firm Oxitec, the mosquitoes seem to be working.

The modified mosquitoes carry a synthetic self-limiting gene that prevents female offspring from surviving. This is important, because only the females bite and transmit disease. In a new study, scientists at the company showed that their engineered insects were able to slash the local population of Aedes aegypti by up to 96 percent over 11 months in the neighborhoods where they were released.

“This is an area with high levels of Aedes aegypti, and they periodically have outbreaks of dengue,” says Nathan Rose, head of malaria programs at Oxitec. In fact, this summer the Brazilian Ministry of Health reported that dengue fever was continuing to spread in all five regions of the country. Between January 1 and May 31, Brazil had more than 1.1 million cases—an increase of 198 percent compared to the same period in 2021. In those five months, the disease, which causes high fever, rash, and muscle and joint pain, killed 504 people.

For the study, which was conducted in 2018 and 2019, the company chose four densely populated neighborhoods with high levels of Aedes aegypti. In two, scientists released a “dose” of 100 male mosquitoes per resident per week. In the others, they cranked that up to 500.

The modified males mate with wild females, but the self-limiting gene prevents female progeny from surviving. This gene, which is lab-engineered but based on elements found in E. coli and the herpes simplex virus, causes the female offspring’s cells to produce lots of a protein called tTAV. This interferes with their cells’ ability to produce other essential proteins needed for development. As a result, the females die off before they mature and start biting. Male offspring survive, carrying a copy of the self-limiting gene that they can then pass on.

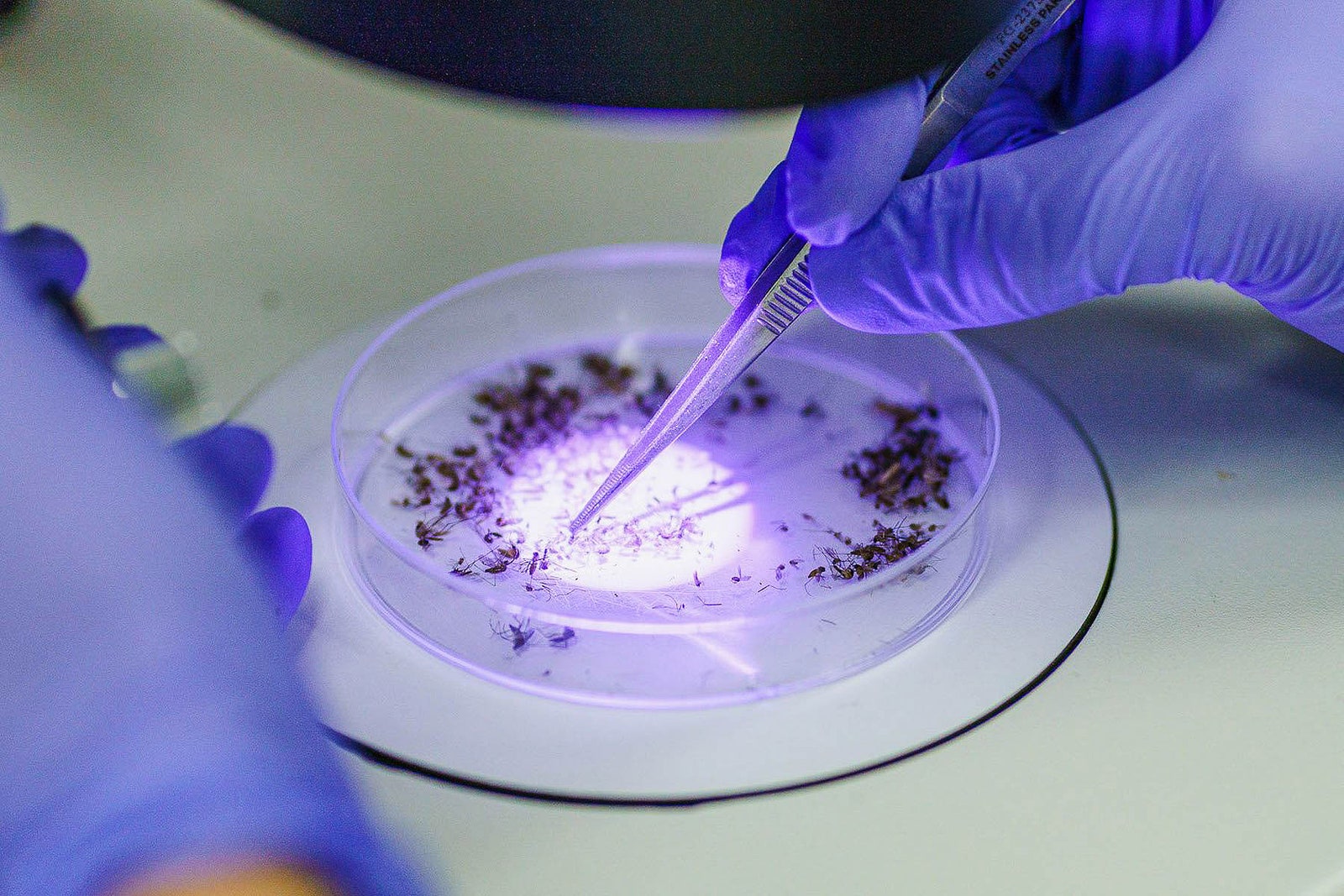

To determine just how effective these self-limiting male mosquitoes are, scientists have to gauge the local mosquito population before and after the experiment. They either lure, trap, and tally the number of adult mosquitoes in an area, or set out traps filled with water, and then count the eggs females lay in them. Then they extrapolate to get a population estimate. (The Oxitec team used the egg method.)

This study found that during the peak mosquito season, which lasts from November to April in Brazil, treated mosquito populations were suppressed by an average of 88 percent, and in some cases up to 96 percent, compared to those in an untreated neighborhood that acted as a control.

Photograph: Alexandre Carvalho/Oxitec

Interestingly, the dose of the mosquitoes didn’t seem to make a difference in how effective the method was. “There’s a limited number of female mosquitoes which are out there in the environment, and the important thing is that you maximize their chance of meeting one of these released ‘friendly’ male mosquitoes, as we call them,” Rose says. “We think as long as you have more of these friendly male mosquitoes out in the environment than the wild males, the chances are much more likely that the female will find one of the Oxitec male mosquitoes.” In fact, Rose thinks it will be possible to release even fewer mosquitoes for a similar effect.

Like other countries, Brazil conducts large-scale sprayings of insecticides to keep problematic mosquitoes under control. Aedes aegypti was once eradicated in much of South America after widespread use of the toxin DDT in the 1950s. But once the chemical’s harmful health and environmental effects came to light, spraying was stopped and the mosquito soon rebounded. Today, pyrethroids are commonly used for mosquito control, but mosquitos are increasingly acquiring resistance to them.