Our understanding of the mechanism of the disease is shifting, too, in a way that could make early diagnosis more valuable. Dementia has a very long preclinical phase—as long as 20 years, in some cases—during which scans and blood tests can detect subtle changes but symptoms have not yet appeared.

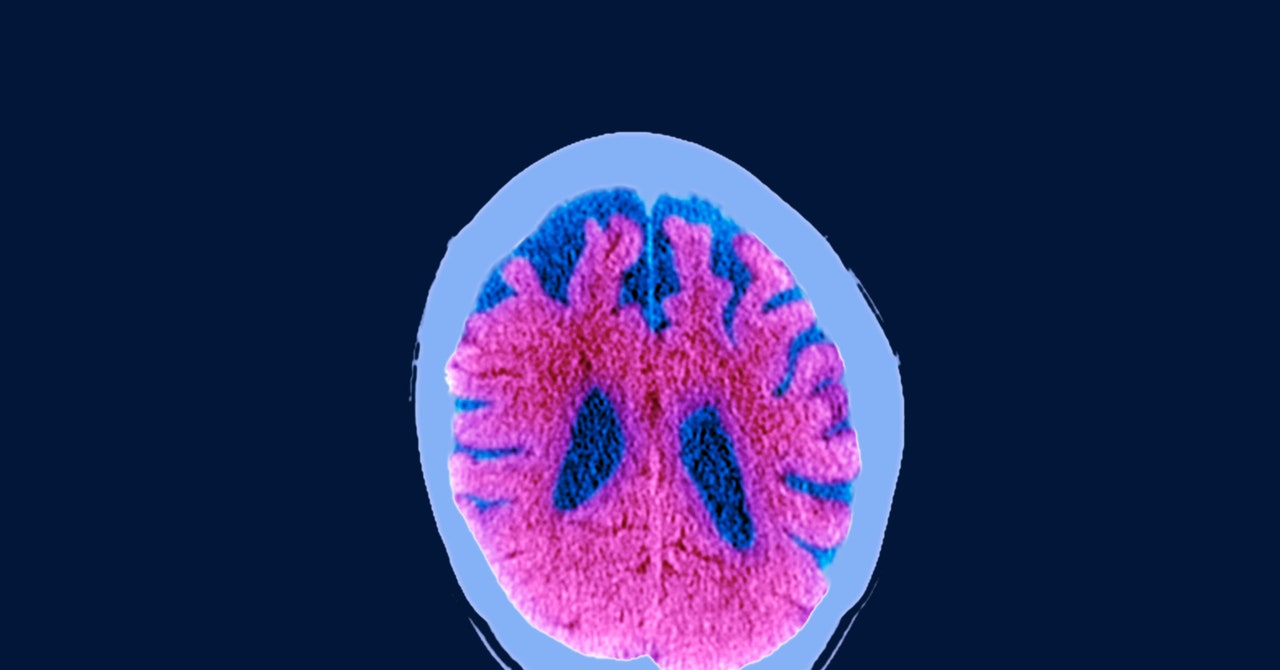

Two proteins start to show up in the brains of patients with dementia during this window: tau and amyloid. Researchers have struggled for years to untangle exactly what role they play, but now some think they have an answer. In dementia and Alzheimer’s patients, amyloid forms tangles and plaques in the spaces between brain cells. The theory is that once it builds up to a certain level, it triggers tau protein—which is normally part of the scaffolding of neurons—to convert from a normal to a toxic state. That’s what causes the bulk of the symptoms, by killing cells and interfering with neurons’ ability to send clear signals.

In June 2021, the FDA granted accelerated approval to aducanumab, the first new drug for Alzheimer’s disease in 18 years. It’s designed to stick to amyloid molecules and make it easier for the immune system to clear them out. But it’s a controversial approach, because in the past drug treatments aimed at clearing amyloid have failed to make much of a difference.

In the emerging theory of dementia, however, the timing of the intervention may be critically important. With better early detection, drugs like aducanumab could be given when they still have time to make a difference. “If you remove the amyloid at a very early stage, maybe that’s when the real benefit happens,” says Koychev. If amyloid could be cleared from the brain before it triggers tau to turn toxic, perhaps the worst effects could be delayed or avoided altogether.

Easy-to-use digital tests could be combined with brain scans and blood tests to help researchers build a map of exactly how amyloid and tau proteins correlate with cognitive impairments—and whether clearing them makes a difference. Rather than a blanket approach of screening everyone, Koychev suggests targeting those in the most at-risk groups with regular assessments.

He notes, however, that there is still a lot of disagreement in the field, and there are serious doubts over whether the new drug for Alzheimer’s will work as hoped. But it has reinvigorated research after what Habibi calls a “long period of drought” in a field that has lagged behind cancer in terms of investment and interest from pharmaceutical companies. Dening thinks that is due to a combination of factors—the stigma of the disease, the advanced age of the people who usually get it, and a fatalist “well, that’s just what happens when you get old” attitude.

Things are finally changing as a large and affluent demographic cohort moves into the age bracket where the risk is the highest. Tests like the ICA are targeted at them, but Koychev hopes they will also “democratize access to brain health.”

Because they’re digital and only semi-supervised, they can be taken anywhere you can take an iPad. That means they can reach people who have been left out of traditional studies into the condition, which are often populated by groups of volunteers that don’t accurately reflect the underlying population. They can also be taken more often, to build a picture of an individual’s cognitive performance over time—Cognetivity has a separate iPhone app called OptiMind designed for home-tests that aims to do just that.

We may still lack good treatments for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but the ability to detect them earlier could change our attitude toward them, which in itself may improve our understanding and spark investment in the solutions we need. “Brain health will become something people monitor and look after, just as you look after your physical health,” says Koychev.

More Great WIRED Stories