More than a decade after the last space shuttle took flight, NASA’s almost ready to launch a rocket once again. The Space Launch System, the most powerful rocket ever built, is designed to bring the Artemis missions to the moon, starting with Artemis I this spring. But before the big show, engineers have to conduct a battery of tests, putting the fully stacked SLS rocket on the launchpad and running a “wet dress rehearsal” that includes a practice countdown.

NASA engineers plan for the rocket to make its debut on Thursday at 5 pm Eastern time. It will then roll out of the Vehicle Assembly Building and be ferried to Launch Complex 39B at Kennedy Space Center on Florida’s east coast. Engineers and technicians will run a series of prelaunch tests through April 3, and if SLS passes, NASA can set the launch date for the Artemis I mission. But with increasing scrutiny of cost overruns and delays, and with so much effort and funding invested in the Artemis moon program—a test run and staging ground for eventually sending astronauts to Mars—there’s a lot riding on that rocket.

“This is a very exciting time. It’s going to be a wonderful sight when we see that amazing Artemis vehicle cross the threshold of the VAB and we see it outside of that building for the very first time. I think it will be breathtaking and something really special,” said Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, Artemis launch director at Kennedy Space Center, at a press conference on Monday. NASA has already completed some tests, including of the ground and communication systems and of the countdown sequencing. “All of this is leading up to our readiness to roll,” she said.

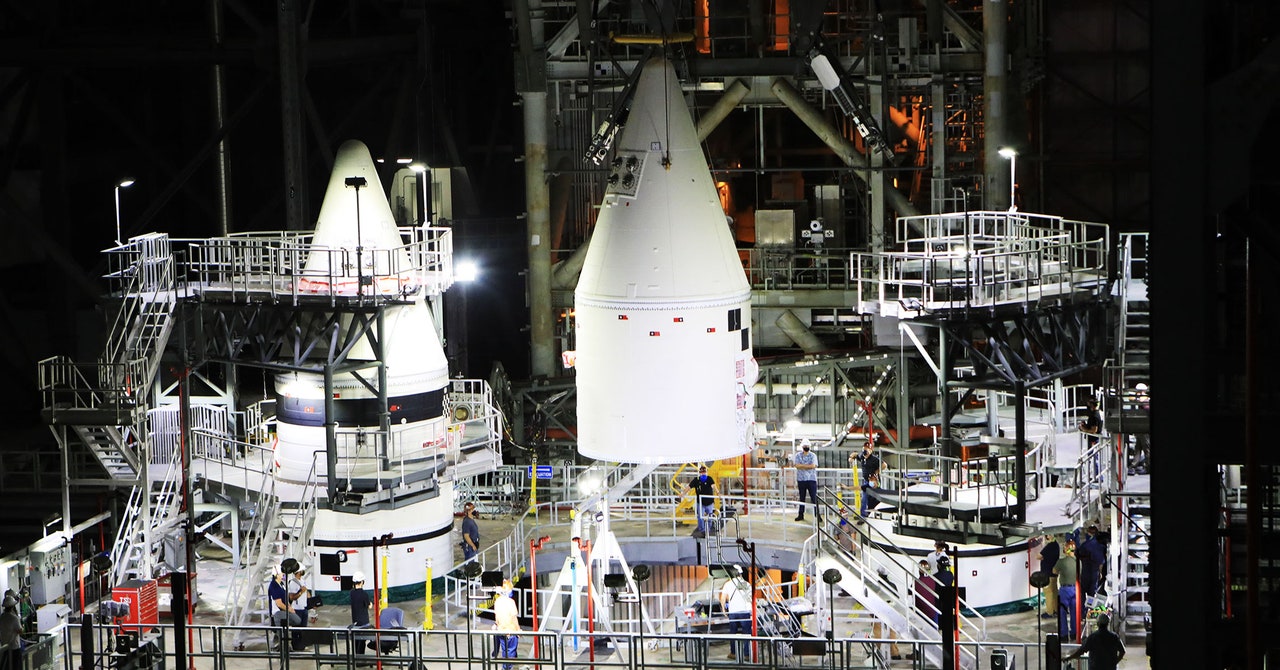

For the Artemis I mission, the combined SLS rocket and Orion capsule spacecraft stand 322 feet tall—taller even than the Statue of Liberty. NASA employed multiple contractors for the rocket’s construction. It includes a pair of white, shuttle-derived solid rocket boosters, which Northrop Grumman upgraded for SLS. Boeing built the huge orange core stage rocket, equipped with engines made by Aerojet Rocketdyne. The European Space Agency is a partner on the Artemis program, and, contracting with Airbus, it built service modules for Orion. Subsequent Artemis missions will use even larger core stages and have the capacity to carry a 46-ton payload, including Orion and its crew, to the moon or Mars.

The first thing everyone will see on Thursday will be the giant rocket verrry slooowwwly rolling out on a *Star Wars–*style crawler, a moving platform with tanklike treads, at a max speed of 0.8 miles per hour. Engineers will collect data while en route, checking whether the little vibrations from the crawler’s motions affect the rocket in any way. After a six-hour drive, it will arrive at the launchpad that night. Launch Complex 39B is a hallowed spot. It previously hosted 53 shuttle launches, and before that those of the Saturn V rockets, super heavy-lift vehicles that carried the Apollo spacecraft to the moon in the 1960s and ’70s.

Once SLS arrives, engineers will have about two weeks to complete their final tests. Those will include: checking interfaces between the core stage, boosters, and ground systems; a booster thrust control test; and testing radio frequency antennas that allow communication between mission control, the rocket, and Orion. Everything will culminate with what’s called the wet dress rehearsal, when engineers will fuel up the propellant tanks with super-cooled liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen and conduct a launch countdown—but stop at T-10 seconds.