This story originally appeared on Undark and is part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

When Hurricane Ike made landfall in 2008, Bill Merrell took shelter on the second floor of a historic brick building in downtown Galveston, Texas, along with his wife, their daughter, their grandson, and two Chihuahuas. Sustained winds of 110 mph lashed the building. Seawater flooded the ground floor to a depth of over 8 feet. Once, in the night, Merrell caught glimpses of a near-full moon and realized they had entered the hurricane’s eye.

Years earlier, Merrell, a physical oceanographer at Texas A&M University at Galveston, had toured the gigantic Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier, a nearly 6-mile-long bulwark that prevents North Sea storms from flooding the southern Dutch coast. As Ike roared outside, Merrell kept thinking about the barrier. “The next morning, I started sketching what I thought would look reasonable here,” he said, “and it turned out to be pretty close to what the Dutch would have done.”

These sketches were the beginning of the Ike Dike, a proposal for a coastal barrier intended to protect Galveston Bay. The core idea: combining huge gates across the main inlet into the Bay from the Gulf of Mexico, known as Bolivar Roads, with many miles of high seawalls.

Just across from Galveston, at least 15 people died that night on the Bolivar Peninsula, and the storm destroyed some 3,600 homes there. Bodies were still missing the next year when Merrell began to promote the Ike Dike, but, he said, the idea “was really ridiculed pretty universally.” Politicians disliked its costs, environmentalists worried about its impacts, and no one was convinced that it would work.

Merrell persisted. Returning to the Netherlands, he visited experts at Delft University and enlisted their support. Over the next few years, Dutch and US academic researchers carried out dozens of studies on Galveston Bay options, while Merrell and his allies gathered support from local communities, business leaders, and politicians.

In 2014, the US Army Corps of Engineers partnered with the state to study Ike Dike-like alternatives for Galveston Bay. After many iterations, bills to establish a governing structure for the $26.2 billion barrier proposal, which the Corps developed alongside the Texas General Land Office, recently passed both the Texas House and Senate. In September, the Corps will deliver their recommendations to the US Congress, which will need to approve funding for the project.

No one can guess the barrier proposal’s exact fate, given its enormous price tag. And as sea levels rise and storms intensify with global climate change, Houston is far from the only US coastal metropolitan region at serious risk. Multibillion-dollar coastal megaprojects already are underway or under consideration from San Francisco to Miami to New York City.

President Joe Biden’s new $2 trillion national infrastructure initiative specifically calls for projects on the country’s embattled coasts. The initiative for Houston, the fifth-largest US metro area and the vulnerable heart of the petrochemical industry, spotlights the tough decisions for coastal megaprojects, which must balance societal needs, engineering capabilities, environmental protections, and costs.

Meanwhile, the seas keep rising. “It’s a significant tension between the need to address these issues and do it quickly,” said Carly Foster, a resilience expert at the global design consultancy Arcadis, “and also do it right.”

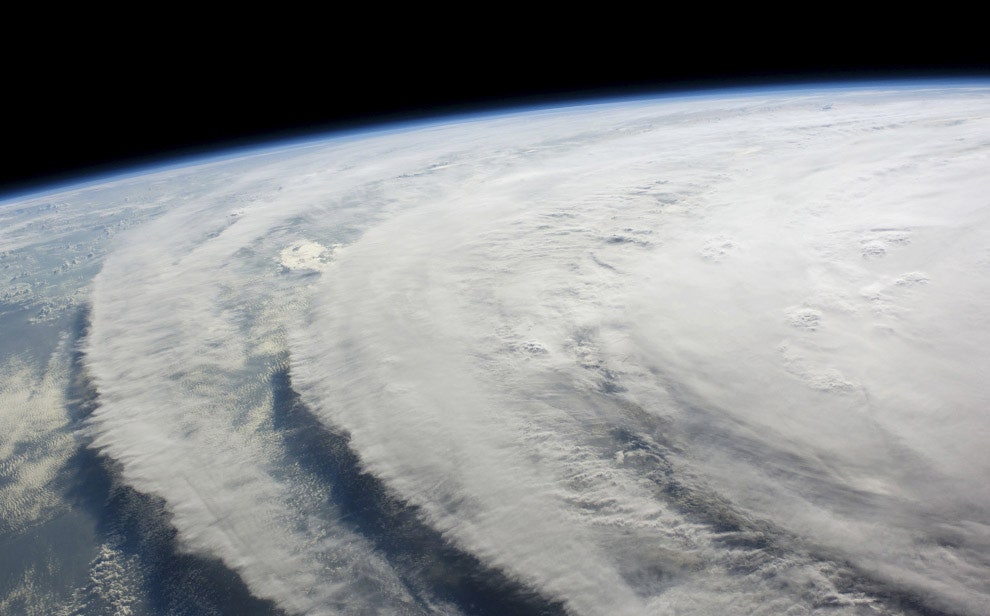

Hurricane Ike, viewed 220 miles above Earth from the International Space Station, on Sept. 10, 2008.

Photograph: NASA