reader comments

57 with 44 posters participating

Dozens of movie production companies sued LiquidVPN this year over the VPN provider’s marketing efforts that could be perceived as promoting piracy. These companies, which are now seeking $10 million in damages, claim that the “no log” policy of LiquidVPN is not a valid excuse, as the VPN provider actively chose to not keep logs.

And because LiquidVPN’s lawyers failed to show up in court, the plaintiffs are pushing a motion for a default judgment to be granted.

Fiery marketing that backfired

At what point does a netizen’s right to privacy and anonymity cease is the crux of the lawsuit brought forth against LiquidVPN. LiquidVPN is a no-log VPN provider that, over the course of its business activities, has been observed to… almost encourage online piracy.

Many Internet users who rely on technologies like logless VPNs and Tor may do so to remain untraceable, for reasons ranging from safeguarding their privacy to protecting someone to browsing the dark web to participating in activities deemed questionable, legally or ethically. As such, much like Internet providers (ISPs), VPN companies are seen as “neutral” service agents and may benefit from the “safe harbor” provisions of a US copyright law called the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, or DMCA. Online service providers can claim “safe harbor” protections under DMCA provided that they timely block access to the infringing materials reported to them by copyright holders.

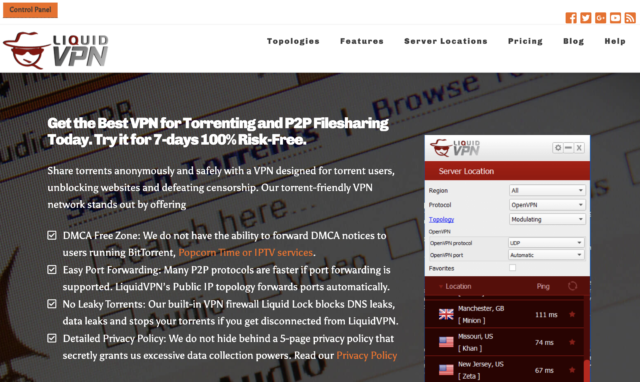

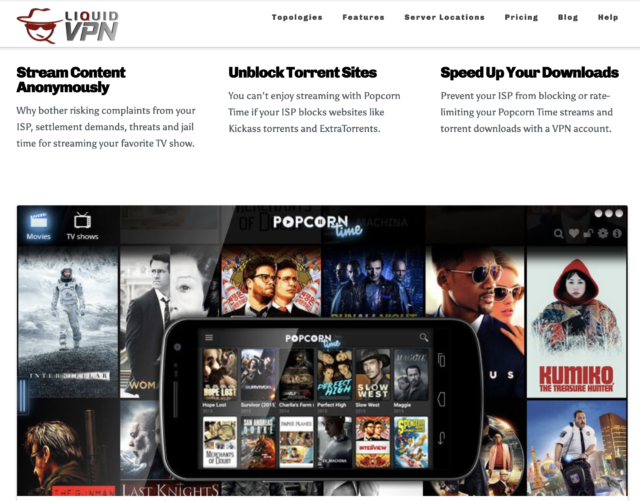

But LiquidVPN’s business model was a fierce one, thriving on the fence of the law. In webpages seen by Ars, the VPN company boasted itself as “the best VPN for torrenting” that would also let you “unblock ISP banned streams,” otherwise restricted due to copyright takedown requests.

Furthermore, LiquidVPN customers were really in for a treat with “High Quality Popcorn Time Streams” thrown into the mix. And, of course, this was all a “DMCA Free Zone,” since, much like any logless VPN provider, Liquid did not have the ability to forward DMCA notices to users downloading infringing content. Except, Liquid listed all of these features on its website explicitly and glamorized all of the possibilities:

And imagine doing all these things seven days of the week without the risk of getting caught by your ISP or anyone else, reassured the VPN provider with a “full-refund” guarantee.

Transparency can be a good thing when presenting your product, except when your marketing claims surpass the legal gray area.

LiquidVPN disappears, in court and online

Unsurprisingly, in March this year, several filmmakers filed a lawsuit with the Florida District Court against LiquidVPN. This month, these plaintiffs are asking the court to issue a default judgment against LiquidVPN for the defendant’s failure to plead or show up at the most recent court hearing.

According to court documents, movie production firms argue LiquidVPN should not be extended “safe harbor” protections, as the defendant didn’t establish a repeat-infringer policy or appoint a registered DMCA agent. The ask for $9,900,000 comprises the maximum statutory damage amount of $150,000 for each of the 66 works listed in the complaint. Additionally, $1,650,000 has been sought against LiquidVPN for “secondary liability as to DMCA violations.”

reported on the development and notes that “Popcorn Time” is a trademark of one of the plaintiffs: Hawaii-based 42 Ventures LLC, which is owned and operated by intellectual property lawyer Kerry Culpepper. So, that intertwines trademark matters with a copyright lawsuit.

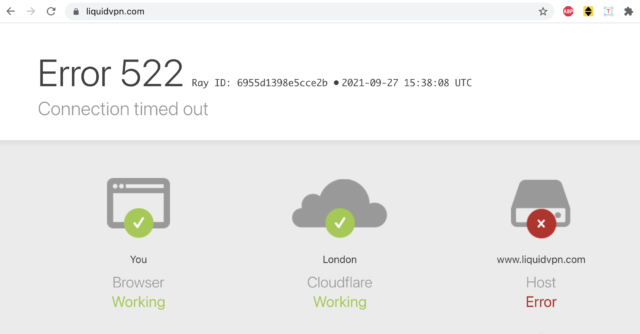

The asks don’t stop there, however. The list of demands extends for LiquidVPN to permanently suspend accounts of repeat infringers, dismissing their “no log” policy. But the face of the LiquidVPN website is already nowhere to be seen. For weeks, the homepage has been unreachable, although the client area remains accessible.

Previously, the plaintiffs had sued the Californian hosting provider Quadranet for leasing their servers to LiquidVPN. Predictably, Quadranet requested that the court dismiss the lawsuit based on frivolous claims. The hosting provider believes plaintiffs had sued them “for tactical leverage only – not because Quadranet directly infringed Plaintiffs’ rights, allegations.”

Incidents like these could set interesting future precedents for otherwise “neutral” providers of online services. Nearly all of the features marketed by LiquidVPN represent activities that, from a technical standpoint, could be conducted by users of virtually any VPN product. And any privacy-cautious person would opt for a “no log” VPN provider over one that keeps traffic logs. In such cases, where does the liability end for providers? For the otherwise benign VPN providers who intend to provide services in good faith and a fair manner, could they still be slapped with DMCA notices and taken to court? And more importantly, what does it mean for honest users?