This situation can also arise when treating ectopic pregnancies; in some edge cases, the fetus can grow to the point where cardiac activity is detected. But, in all cases, an ectopic pregnancy “can never result in childbirth,” De-Lin says emphatically, since the fetus cannot survive outside of the uterus. The standard of care for an ectopic pregnancy is to end it as soon as possible, either through surgery or by administering methotrexate, a drug that stops the cluster of fetal cells from further dividing.

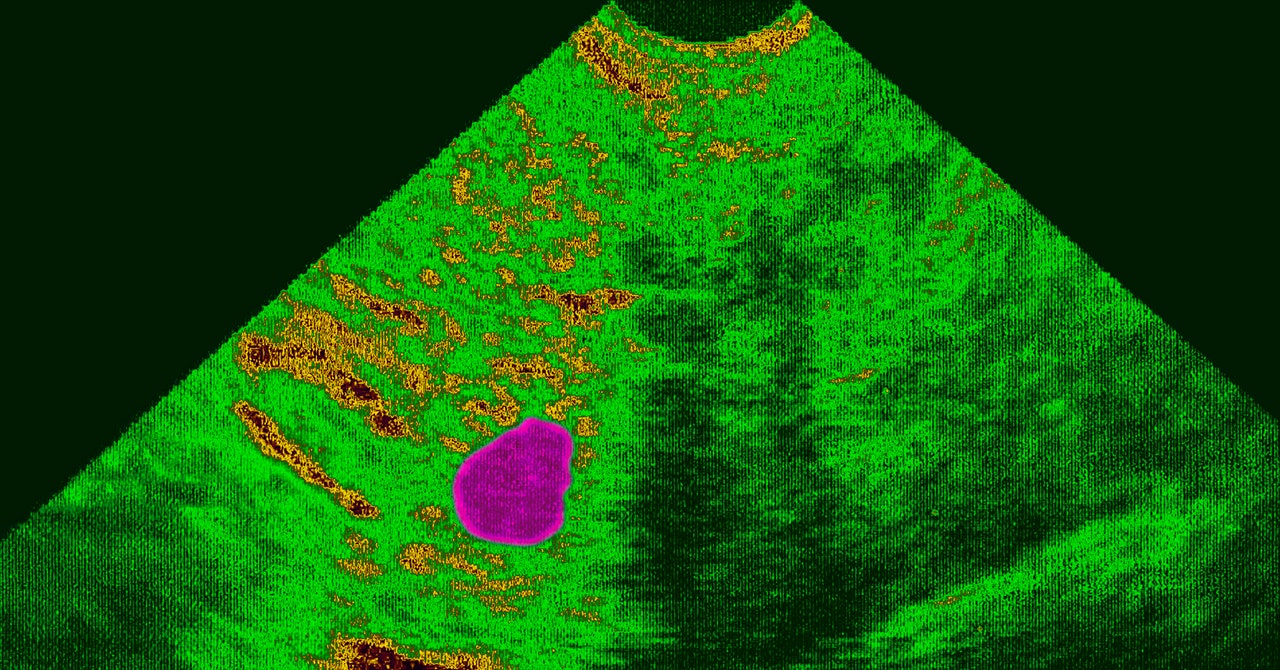

To diagnose an ectopic pregnancy, physicians will look at trends of beta HCG levels—a hormone present in a pregnant person’s blood or urine that, when charted over time, can help determine whether a pregnancy is abnormal. They will also look at ultrasound: If the fetus is explicitly detected to be outside of the uterus, then an ectopic pregnancy is quickly diagnosed.

But as Jennifer Kerns, an obstetrician and gynecologist at UC San Francisco, says, not all these cases are “clear-cut.” In some instances, physicians are unsure whether the pregnancy is a failed intrauterine pregnancy (where fetal viability is not detected inside the uterus), an ectopic pregnancy that just wasn’t detected yet on the ultrasound, or another type of abnormal pregnancy. In this situation, having a viable pregnancy is exceedingly rare, and it can be dangerous for it to progress. To diagnose what went wrong, the doctor can proceed with a uterine aspiration, then look at the removed tissue underneath a microscope. But because this method counts as an abortive procedure, states with tough post-Roe laws are making it harder for doctors to use it as a diagnostic tool.

“Some people are going to feel quite nervous about providing evidence-based medical care, which might be a uterine aspiration, for a condition that could possibly be an ectopic pregnancy, as part of the diagnostic procedure that you do to understand if it’s an ectopic or not,” Kerns says. “Delaying that care is really putting the person at risk of serious morbidity and mortality.”

Without intervention and removal of the ectopic pregnancy, the tissue can “keep growing and can actually cause the fallopian tube to rupture, and it can cause really catastrophic, life-threatening, intra-abdominal bleeding,” says Addante.

Despite these serious consequences, Addante is concerned that, under the guidelines of state laws that followed Roe’s overturn, physicians will be “very reluctant to offer what is really standard-of-care medicine, because they’re afraid of the criminal liability that they might hold.” Restricting abortive procedures unless there is a “medical emergency” or the life of the pregnant person is threatened is very nebulous. It makes it hard for doctors to know when medical intervention becomes OK, particularly when trying to diagnose whether something is a failed intrauterine pregnancy or an ectopic pregnancy. “If it is an intrauterine pregnancy, and you haven’t 100 percent proven that it was a failed intrauterine pregnancy, in today’s world you might be accused of interrupting a normal intrauterine pregnancy,” Addante says. “This is where having to think defensively really interferes with clinical judgment.”

While some state laws contain written exceptions for medical emergencies (including miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies), the overall lack of clarity can cause physicians to proceed cautiously rather than intervene immediately to mitigate risk, De-Lin says. She points out that these regulations seem to be written only with healthy patients and healthy pregnancies in mind. They don’t “leave any room for the broad array of pregnancy-related conditions that may be dangerous to the health of the person carrying the pregnancy,” she says.

Thinking defensively, waiting to intervene until the patient presents with severe medical complications—these are factors that are suddenly, horribly, becoming real situations. Another problem, De-Lin says, is time: Patients who travel across state lines to seek a diagnosis at her clinic sometimes must return to their home states the next day, limiting her ability to provide long-term care if their pregnancy develops serious problems. “There are certain cases where it’s hard to tell if it’s just an early pregnancy, is it an ectopic, is it a miscarriage?” she says. “We need some time and monitoring to figure those things out.” She notes that although she tries to coordinate follow-up care with other Planned Parenthoods across the country, “it is a logistical nightmare sometimes.”

Addante previously worked in Missouri, at a time when state had a 72-hour waiting period between initial counseling and when a patient was allowed to have an abortion. She sometimes had to decide whether the patient was sick enough to waive that waiting period. “One of the most difficult things I have ever experienced as a provider is having to look at a patient and say: ‘I cannot take care of you, not because I don’t know how to but because I am not allowed to,’” she says. “It’s devastating.”

Missouri now bans all abortions except in medical emergencies, and Addante worries about her former colleagues, some of whom, she says, have been told not to counsel patients on all treatment options—which can include abortive procedures. That, Addante says, “just violates every oath we took in this field.”