As a physical therapist in Shanghai, Zheng Wang worked with people recovering from strokes after their brains had been damaged by oxygen deprivation. They usually followed a predictable recovery pattern, making lots of progress over the first few visits, then hitting a wall. Patients asked when they’d finally feel normal, and Wang told them that they’d get better with time. “But actually,” he remembers, “I knew from the bottom of my heart that they wouldn’t improve much, no matter how hard we tried.”

Meanwhile, halfway across the world, Marc Dalecki, then an associate professor in the School of Kinesiology at Louisiana State University (LSU), couldn’t stop thinking about oxygen. Dalecki spent much of his early career studying scuba diving and remembers divers using nasal cannulas of O2 to help with everything from hypoxia to headaches. He always wondered whether this simple treatment could help neurological patients in rehab. “I promised myself that I would study it when I got my own research lab,” he says.

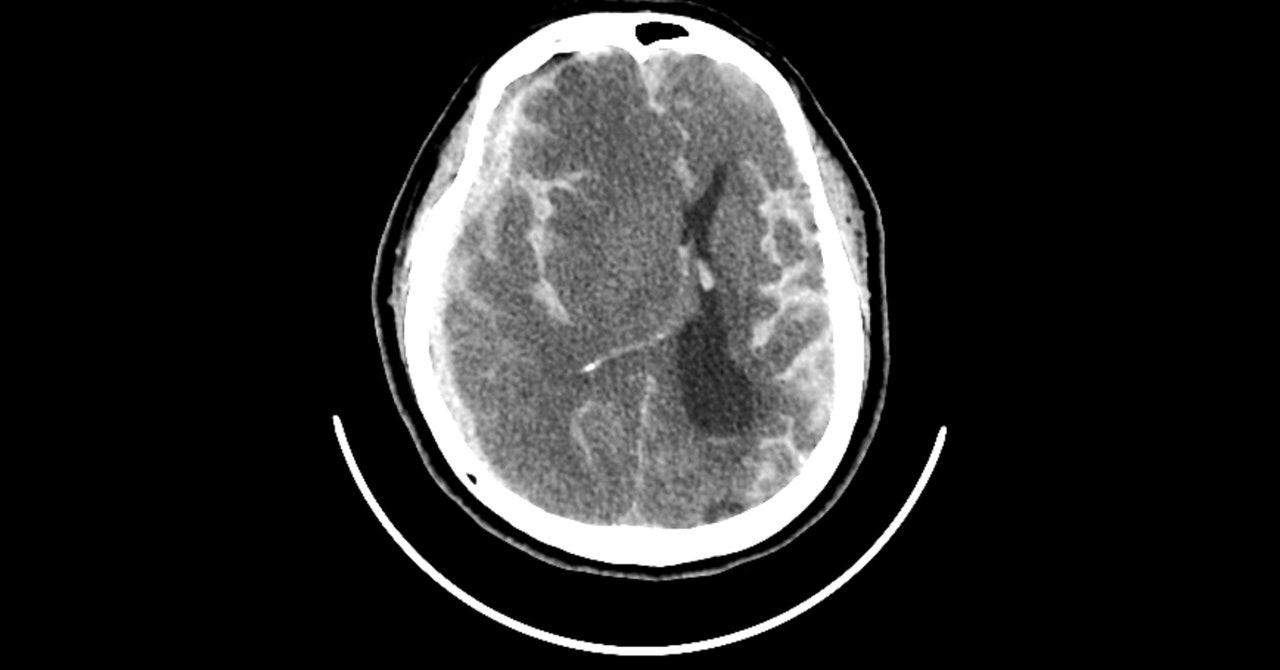

For its relatively small size, the brain consumes a ridiculous amount of power: 20 to 30 percent of the body’s energy at rest. To fuel all of its neurons, the brain depends on oxygen. When someone has a stroke or a head injury, the flow of oxygenated blood to the brain gets disrupted. Starved of oxygen, the brain tissue is damaged, leading to a host of problems with memory, speech, strength, and motor control.

Rehabilitation from brain trauma usually involves working with a physical therapist to relearn motor skills, building up the strength and coordination required for daily activities, like making coffee, writing, and brushing your teeth. Many physical therapists already use high-tech devices to help patients recover faster, from robots that move impaired limbs to virtual reality games that simulate aspects of day-to-day life that can’t be easily replicated in a hospital setting. But Wang and Dalecki both wondered whether oxygen could be the simple, cheap, accessible addition to neurological rehabilitation they’d been looking for. If they could give patients a little extra oxygen during early motor rehab sessions, they thought, it might help them relearn old skills faster.

The two of them joined forces in Dalecki’s lab at LSU, where Wang, frustrated as a clinician, decided to get a PhD in kinesiology. In a study published last week in Frontiers in Neuroscience, their team showed that sniffing pure oxygen while learning a challenging motor task helped healthy young people learn faster and perform better. They think this relatively low-cost, low-risk idea could be used to speed up stroke recovery.

For their study, they recruited 40 healthy young adults to each sit at a desk while wearing a nasal cannula. Their instructions were simple: Hold a stylus at the center of a tablet screen, then drag it to a target that pops up somewhere else, as quickly and efficiently as possible. But after a few trials, the relationship between the stylus and the screen shifted, creating a 60-degree difference between the line a participant thought they drew and the line that actually appeared on the screen. While the volunteers adjusted their line drawing to these new, more challenging circumstances, air started flowing through the cannula. Half of the participants got pure oxygen, while the other half got medical air (essentially an ultra-clean version of regular air). It was a quick blast, only during these few minutes of initial learning. Then the air flow shut off and the screen went back to normal.