Over the next six to eight months, Pearson’s OCD symptoms decreased significantly, and her brain activity triggered the stimulation less often. She told her doctors that before, she was sometimes spending eight hours a day performing compulsions. Now, she estimates that it’s more like 30 minutes. The effects have persisted over the two years since the stimulation has been turned on. “It wasn’t instantaneous. It took a few months to notice changes,” she says. “I slowly started noticing things disappearing from my routine. Then, more things would disappear.”

Pearson doesn’t wash her hands as often, and now her knuckles don’t bleed. Her bedtime routine takes just 15 minutes. The best part, she says, is that her relationships with her friends and family are a lot better. She can enjoy a meal with them without feeling distressed.

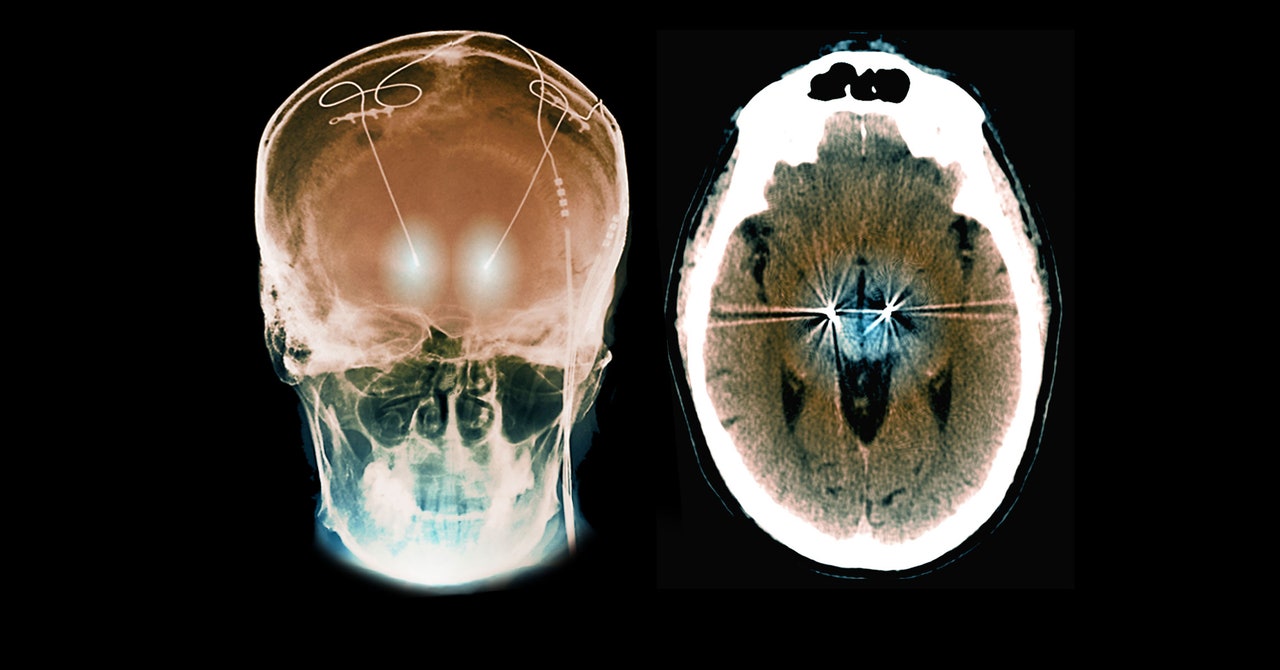

“What this highlights is that OCD is a disorder of the brain, just like epilepsy and Parkinson’s,” Halpern says. “This isn’t a disorder of will. There’s a pathological signal that we’re seeing in the brain.”

Davis says she was initially skeptical of the idea that OCD could be treated with occasional bursts of stimulation. “Often people with OCD have a baseline level of dread or anxiety,” she says. For that reason, she assumed patients would need constant stimulation to keep their brain circuits regulated. Her center has implanted nine OCD patients with traditional DBS devices that provide steady stimulation. Although the Neuron report is just one case study, she thinks it’s impressive that Pearson’s symptoms improved so much with so little stimulation.

If the approach pans out in other patients, Davis sees two potential benefits of personalized stimulation. One is that because the electric current is intermittent, it would boost the life of the device, and patients would need fewer surgeries to replace batteries. Another is that DBS can lose its effectiveness if it’s always on; less frequent stimulation could prevent resistance to it. (Patients have some degree of control with traditional DBS systems, in that they can turn it off, such as when they go to bed.)

Dean McKay, a professor of psychology at Fordham University, wonders whether the neural trigger that was isolated in Pearson’s case would be the same for other people with OCD. “The question is whether or not this would generalize to where you could apply that for other patients,” McKay says. “We really don’t know whether other people would have similar neural signatures.”

There are also subtypes of OCD, McKay says—including contamination obsessions with cleaning compulsions, harm obsessions with checking compulsions, and symmetry obsessions with ordering compulsions—and it’s possible that they might have unique neural signatures.

DBS isn’t a common treatment option for OCD. Most patients are able to manage with therapy or medication. But for some people whose lives are deeply disrupted by the condition, Halpern says DBS has real benefits.

For Pearson, the device has been a lifesaver. “OCD ruled my life,” she says. Some days, she didn’t want to leave the house because it would mean dealing with all her compulsions. “Now, I don’t have to think about that stuff.”

She’s planning to go back to school next year to become a surgical technician. Her goal, she says, is to someday work with the team that gave her her life back.