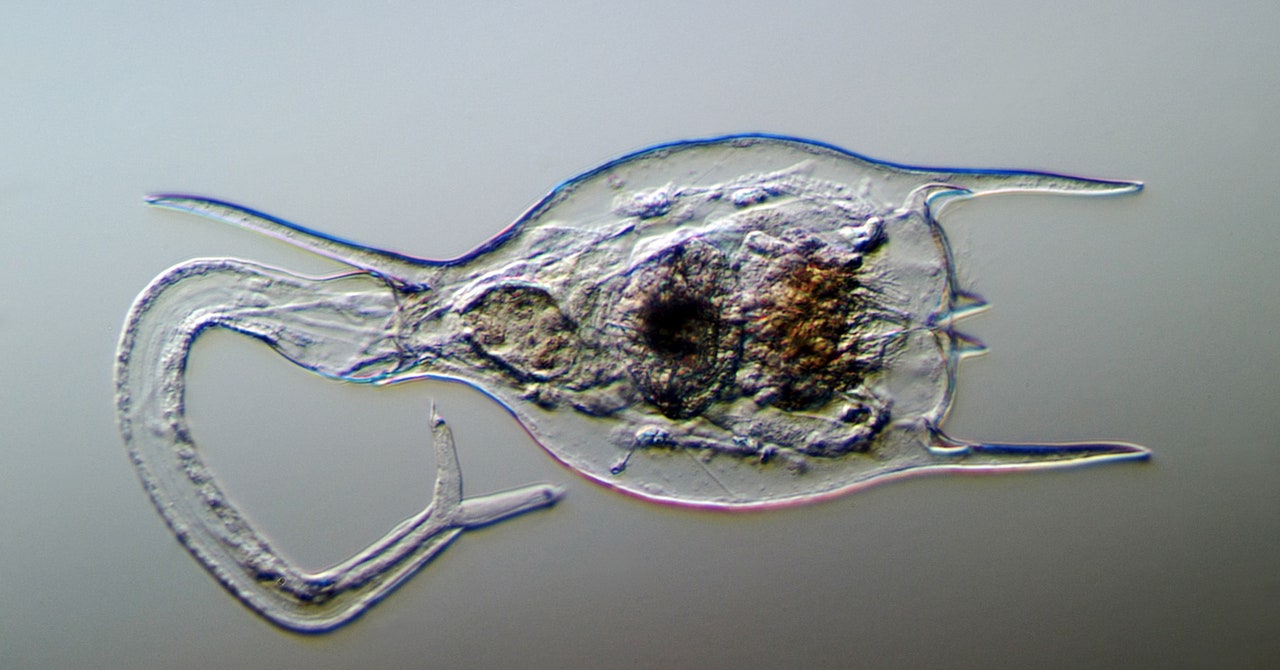

Rotifers are microscopic freshwater-dwelling multicellular organisms. They’re already known to withstand freezing (even in liquid nitrogen), boiling, desiccation, and radiation, and the group has persisted for millions of years without having sex. The humble yet remarkably hardy bdelloid rotifer has now surprised researchers yet again—a recent study unearthed 24,000-year-old Siberian permafrost and found living (or at least revivable) rotifers there. Surviving 24,000 years in a deep freeze is a new record for the species.

Rotifers aren’t the only living organisms to emerge from permafrost or ice. The same researchers behind this latest discovery had previously found roughly 40,000-year-old viable roundworms in the region’s permafrost. Ancient moss, seeds, viruses, and bacteria have all shown impressive longevity on ice, prompting legitimate concern about whether any potentially harmful pathogens may also be released as glaciers and permafrost melt.

Given that bdelloids are generally only a threat to bacteria, algae, and detritus, however, there’s not much need for concern regarding this particular discovery. But as key players in the bottom of the food chain, newly reemerged rotifers indicate that maybe we should think about how species that haven’t been seen for millennia might reintegrate into modern ecosystems.

The Soil Cryology Lab in Pushchino, Russia, has been digging up Siberian permafrost in search of ancient organisms for roughly a decade. The group estimates the age of the organisms it finds by radiocarbon dating the surrounding soil samples (evidence has shown that there is no vertical movement through layers of permafrost). For example, last year, the researchers reported a “frozen zoo” of 35 viable protists (nucleus-containing organisms that are neither animal, plant, nor fungus) that they calculated ranged from hundreds to tens of thousands of years old.

In their most recent discovery, the cryology researchers found the living bdelloids after culturing the soil samples for about one month. Among rotifer classes, bdelloids have the fairly unusual ability to reproduce parthenogenetically—i.e., by cloning—and so the original specimens had already begun to do so. Although the clones made identifying the ancient parent challenging, this did greatly facilitate further investigation of the characteristics and behavior of the unfrozen strain.

Throughout all of the above permafrost studies, there is always the concern of sample contamination by modern-day organisms. Besides using techniques designed to prevent this, the team also addressed this issue by looking at the DNA present in the soil samples, confirming that contamination was highly unlikely. Phylogenetic analysis furthermore showed that the species didn’t match any known modern rotifers, although there is a closely related species found in Belgium.

The team was naturally interested in better understanding the freezing process and gaining insight into just how these rotifers survived for so long. As a first step, the researchers subsequently froze a selection of the cloned rotifers at -15° C for one week and captured videos of the rotifers reviving.

The researchers found that not all of the clones survived. Surprisingly, the clones generally weren’t much more freeze-tolerant than contemporary rotifers from Iceland, Alaska, Europe, North America, and even the Asian and African tropics. They were a little more freeze-tolerant than their closest genetic relative, but the difference was marginal.

The researchers did find that the rotifers could survive a relatively slow freezing process ( around 45 minutes). This is noteworthy because it was gradual enough that ice crystals formed inside of the animals’ cells—a development that is usually catastrophic for living organisms. In fact, protective mechanisms against this are highly sought after by anyone in the business of cryopreservation, making this latest finding especially enticing from that perspective.

Although the authors aren’t quite in that business, they do plan additional experiments to better understand cryptobiosis—the state of almost completely arrested metabolism that made the rotifers’ survival possible. As for research into cryopreservation of larger organisms, the authors suggest that this becomes trickier as the organism in question becomes more complex. That said, rotifers are among the most complicated cryopreserved species so far—complete with organs such as a brain and a gut.