reader comments

35 with

Right now, the destination for the circuit board inside a device you no longer need is almost certainly a gigantic shredder, and that’s the best-case scenario.

Most devices that don’t have resale or reuse value end up going into the shredder—if they even make it into the e-waste stream. After their batteries are (hopefully removed, the shredded boards pass through magnets, water, and incineration, to pull specific minerals and metals out of the boards. The woven fiberglass and epoxy resin the boards were made from aren’t worth much after they’re sliced up, so they end up as waste. That waste is put in landfills, burned, or sometimes just stockpiled.

That’s why, even if it’s still in its earliest stages, something like the Soluboard sounds so promising. UK-based Jiva Materials makes printed circuit boards (PCBs) from natural fibers encased in a non-toxic polymer that dissolves in hot water. That leaves behind whole components previously soldered onto the board, which should be easier to recover.

-

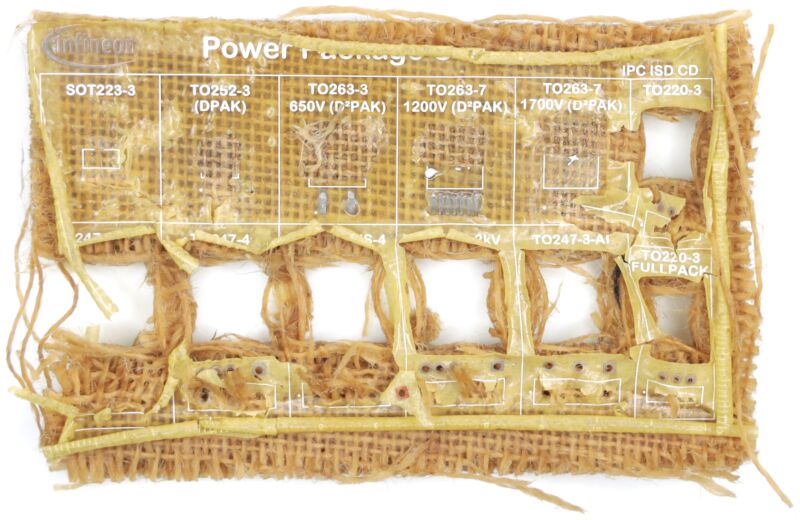

Here’s the “before” pic of an Infineon board assembled on Jiva Technologies’ water-soluble PCB.

-

And here’s the “After,” showing a neat removal of components and a real parking-lot-of-a-Phish-concert vibe.

It’s worth noting, especially for the clumsy among us, that Soluboard’s PCBs aren’t likely to be dissolved by an errant Americano. Soluboards require at least 30 minutes of immersion in roughly 90° Celsius water before delamination starts, the company’s CEO told The Register.

cars, Raspberry Pis, and industrial equipment, has produced demo boards using Soluboard’s tech. The company says it’s also researching the reusability of “discrete power devices at the end of their service life,” which would promote circular reuse and reduce the carbon cost of producing new devices. Infineon estimates that replacing traditional FR-4 PCBs with Soluboard would result in a 60 percent reduction of carbon emissions, or roughly 10.5 kg (23 pounds) of carbon and 620 g (21 ounces) of plastic per square meter of PCB produced. That adds up, given the 18 billion square meters of PCBS manufactured each year, according to Jiva.

Soluboards have had at least one outing in the US, being the core of an “Ecofriendly Mouse” design created by University of Washington researchers in collaboration with Microsoft. That study found comparable data transmission for embedded chips. Chips recovered after board dissolution were baked in an oven to remove moisture, then “reused with no signs of performance loss.”

Soluboards will need far more testing in the wild before widespread use. And electronics recycling, an industry with notably tight margins, may not find as much value in recovering chips from soluble boards as the rosiest scenario might suggest. But any potential advancement in electronics that uses less plastic, and makes things a little easier to break down, is worth a closer look.