This is Part Two of a multipart series that aims to answer the following question: What is the “fundamental value” of Bitcoin? Part One is about the value of scarcity, Part Two — the market moves in bubbles, Part Three — the rate of adoption, and Part Four — the hash rate and the estimated price of Bitcoin.

The market moves in bubbles

In recent months or even years, there’s been a lot of talk about the bubbles developing in the bond markets. Newspapers — both financial and non-financial — talked about it, with specialized television stations and prestigious “macroeconomists” from all over the world discussing how today’s world debt has negative interest rates.

It is financially counterintuitive to have to pay or lend money to someone, even if that person is a state. We are experiencing an absurd situation that has never happened before in the financial market landscape. The main cause is linked to the enormous liquidity injected into the markets by central banks, which they use as funding to avoid their own bankruptcy, only to then, prudently, reverse it back onto the states (they themselves in difficulty).

After all, John Maynard Keynes’s famous phrase reads:

“Financial markets can remain irrational for much longer than you can remain solvent.”

In actuality, this absurdity has made it possible to avoid the bankruptcy of the financial system, so it is welcome, even though it feeds irrational phenomena, such as bond markets with negative yields (and therefore senseless bond prices) and stock markets touching (not all, but most) new highs day after day.

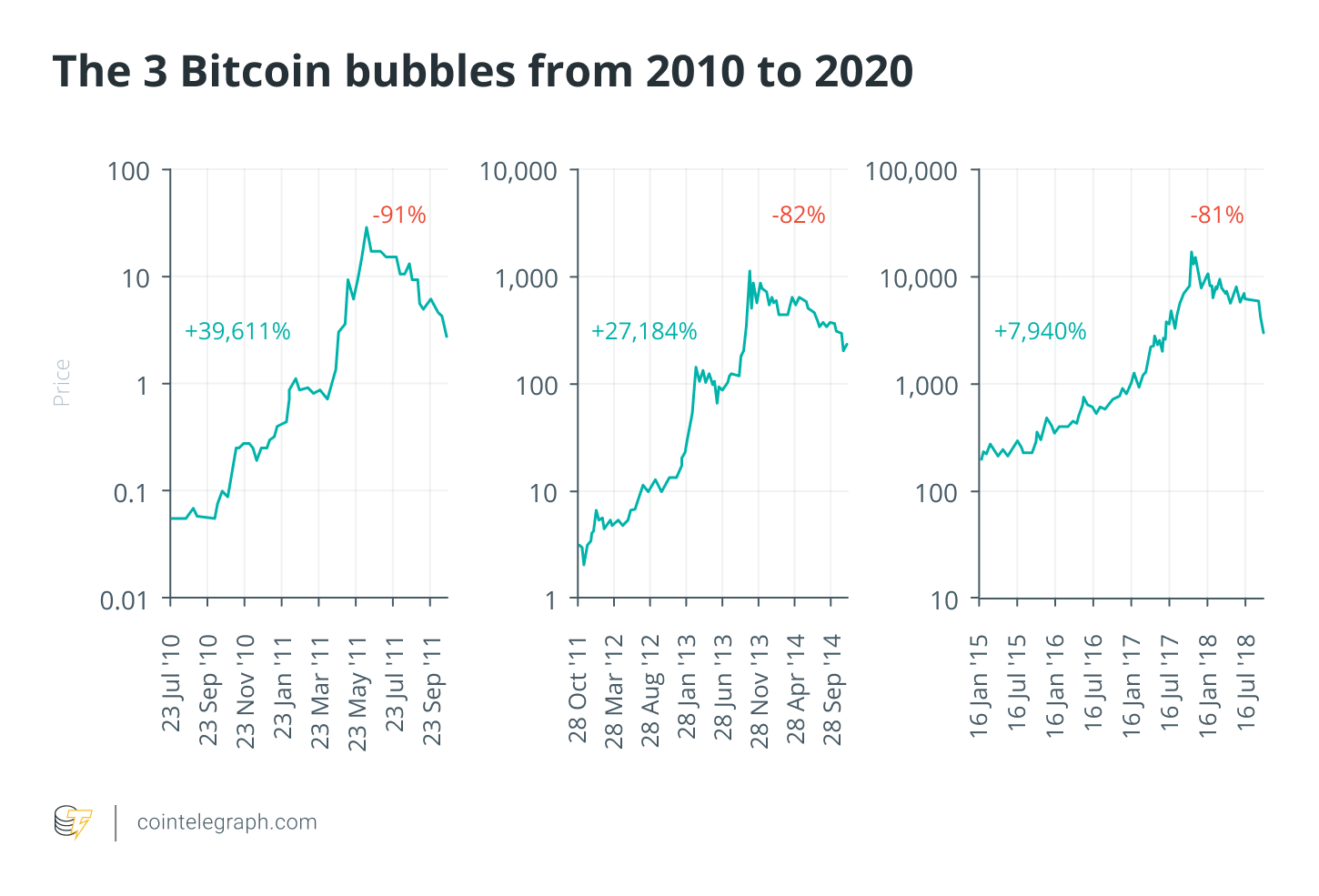

One phenomenon that isn’t actually fueled by central bank money, that everyone labeled a meaningless mega bubble in 2017, is Bitcoin (BTC). The price of Bitcoin rose to a high of $20,000 in December 2017, coinciding with the launch of Bitcoin futures by the Chicago Board Options Exchange and the CME Group, the two largest commodities exchanges in the world, and then hit a minimum of around $3,100 in 2018, effectively losing over 80% of its value.

Does it represent the bursting of a bubble? Sure. Does it represent the end of Bitcoin? Certainly not. Could there be more Bitcoin bubbles in the future? Of course.

As always, we would like to approach the problem as analytically as possible. We reconstructed the table created by the founder of Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto, using Excel, to make sure that Bitcoin was deflationary and not inflationary.

Inflation

The U.S. dollar (and all currencies in the world, truthfully, including the euro), due to inflation, is worth less and less over time. We can better understand the phenomenon if we think about the value of assets. Buying a car 40 years ago cost about 13 times less than it does today, so a nice car that cost $10,000 in 1980 would cost $130,000 today.

This phenomenon is called inflation, and it is induced by a rule that links the total value of goods in the world to the total currency in circulation. If the number of U.S. dollars in circulation doubles, the same goods will tend to cost twice as much. It “will tend” because currency is not a linear phenomenon, and it may take some time to happen.

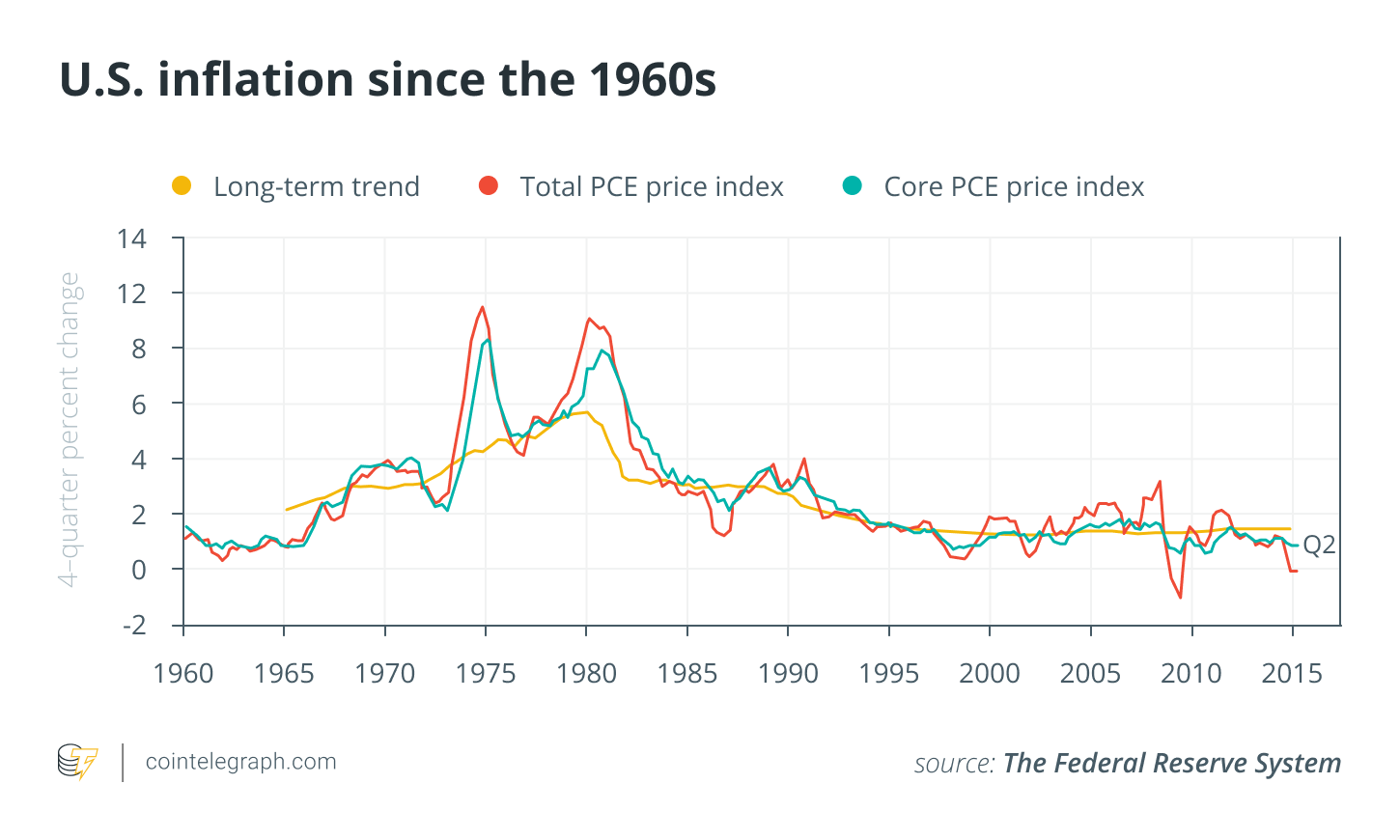

In the 1970s and early 1980s, inflation in the United States reached rates close to 12% per year, creating many difficulties for those who didn’t have the knowledge and the means to counter it.

Deflation

Bitcoin was created with a deflationary logic, more similar to commodities such as gold and silver. This is why it’s considered by many to be the new digital gold, as it has preservation of value characteristics and not those of impoverishment, like the dollar or the euro.

Related: Is Bitcoin a store of value? Experts on BTC as digital gold

Let’s see how it was possible to create, and what the effects resulting from these choices are.

Nakamoto decided that the maximum number of Bitcoin created and available should be 21 million. (The number 21 will occur many times. It is the Greek letter phi, which we will also talk about later). He could have decided to enter a fixed amount of Bitcoin for each block that got mined, but doing so wouldn’t have created the exponential growth effect that characterizes Bitcoin, or at least not as marked as it is today.

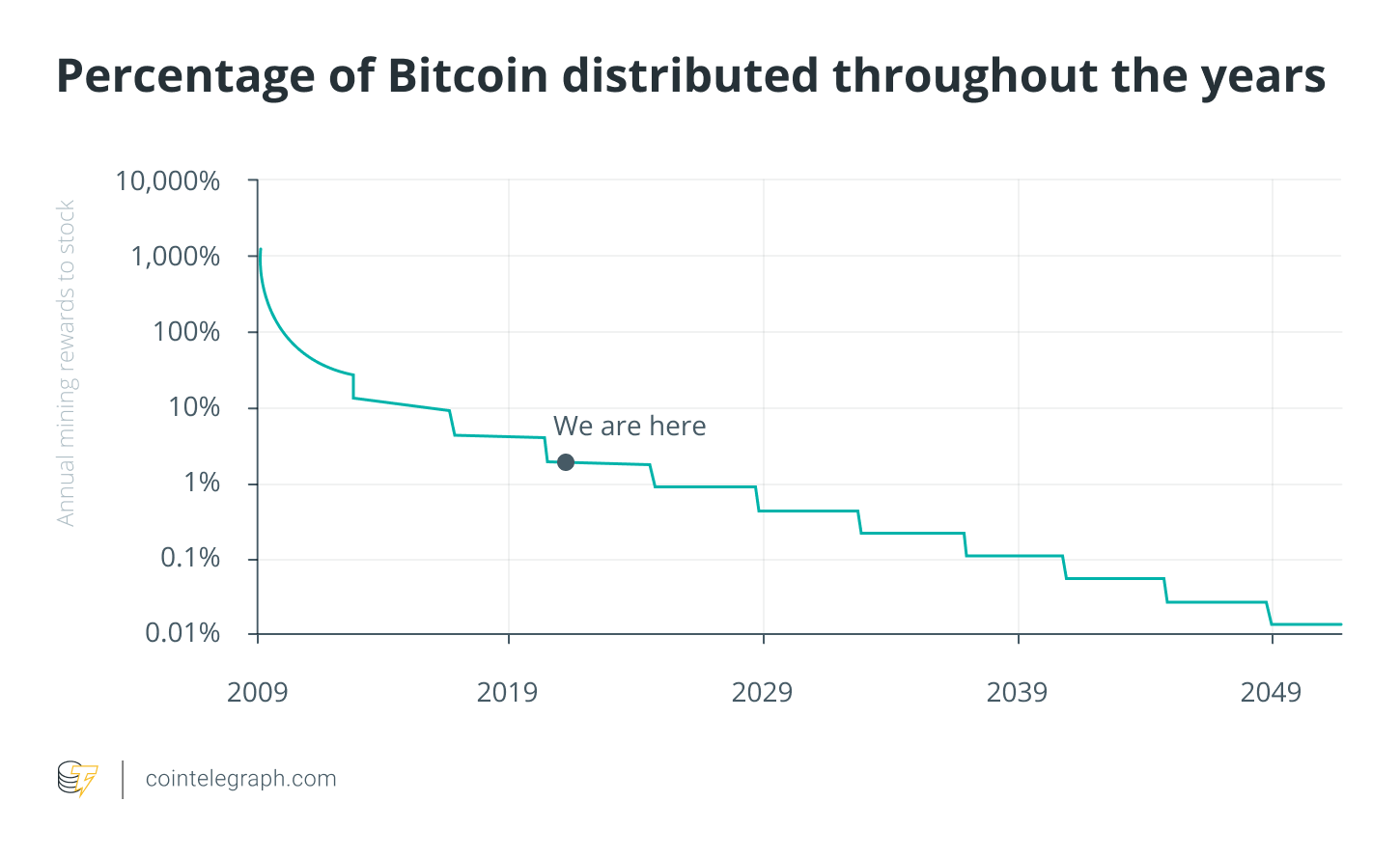

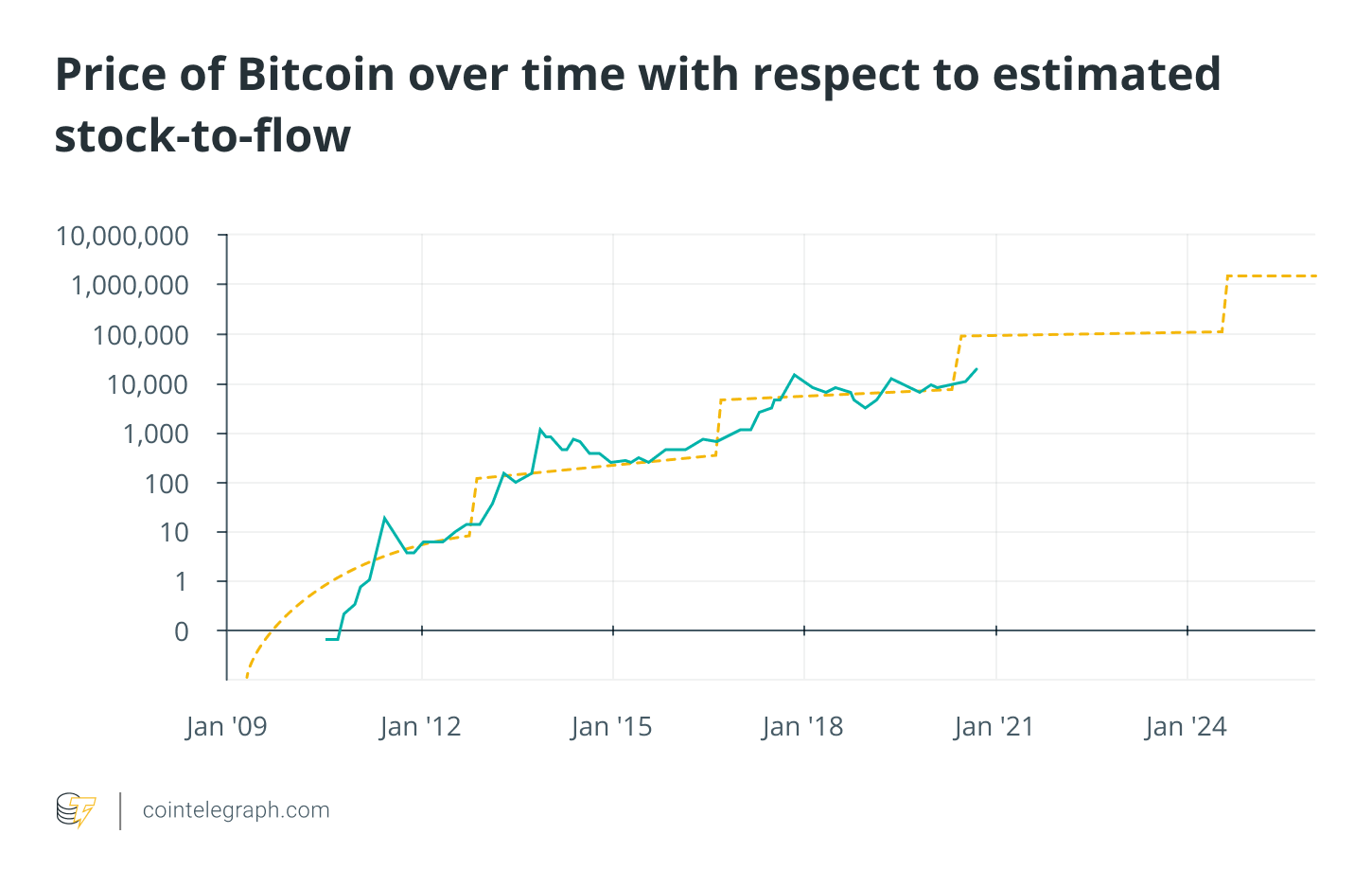

Consequently, he decided to halve the amount of newly issued Bitcoin every four years, to create a very marked and interesting stock-to-flow effect that would push the price higher and higher.

Related: Bitcoin Halving, Explained

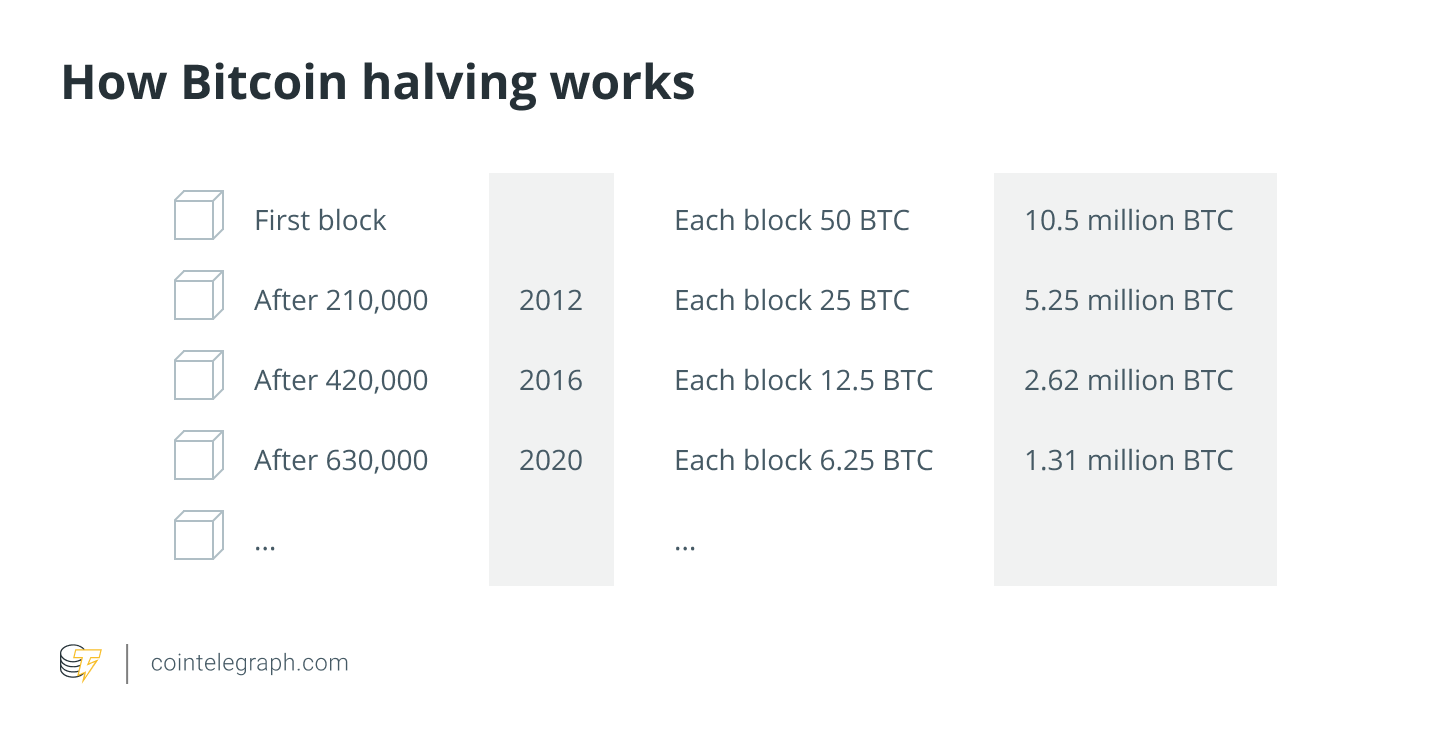

For the first 210,000 blocks, miners were paid 50 BTC for each block written on the distributed ledger, at a time where the value of Bitcoin fluctuated from a few cents up to a few dollars, so the remuneration was not in the least comparable with that of today — neither was it as difficult to win the challenge. In fact, in the early years, simple computers were enough to do the mining.

The first halving took place in 2012 — i.e., from the 210,001st block onward, remuneration was halved to 25 BTC for each writing on the distributed ledger. In 2016, the second halving took place, which brought the remuneration down to 12.5 BTC, and again with the third halving taking place in May 2020, bringing the remuneration for each block to 6.25 Bitcoin, which with a recent price correction of around $40,000 is still around $250,000.

Related: 3 good reasons why $30,000 is probably the bottom for Bitcoin

The next halving is scheduled for 2024, when remuneration will be further cut by 50%. It is set to continue, probably, until 2140, the year in which the last halving is expected, which will distribute less than 1 Bitcoin in the last year.

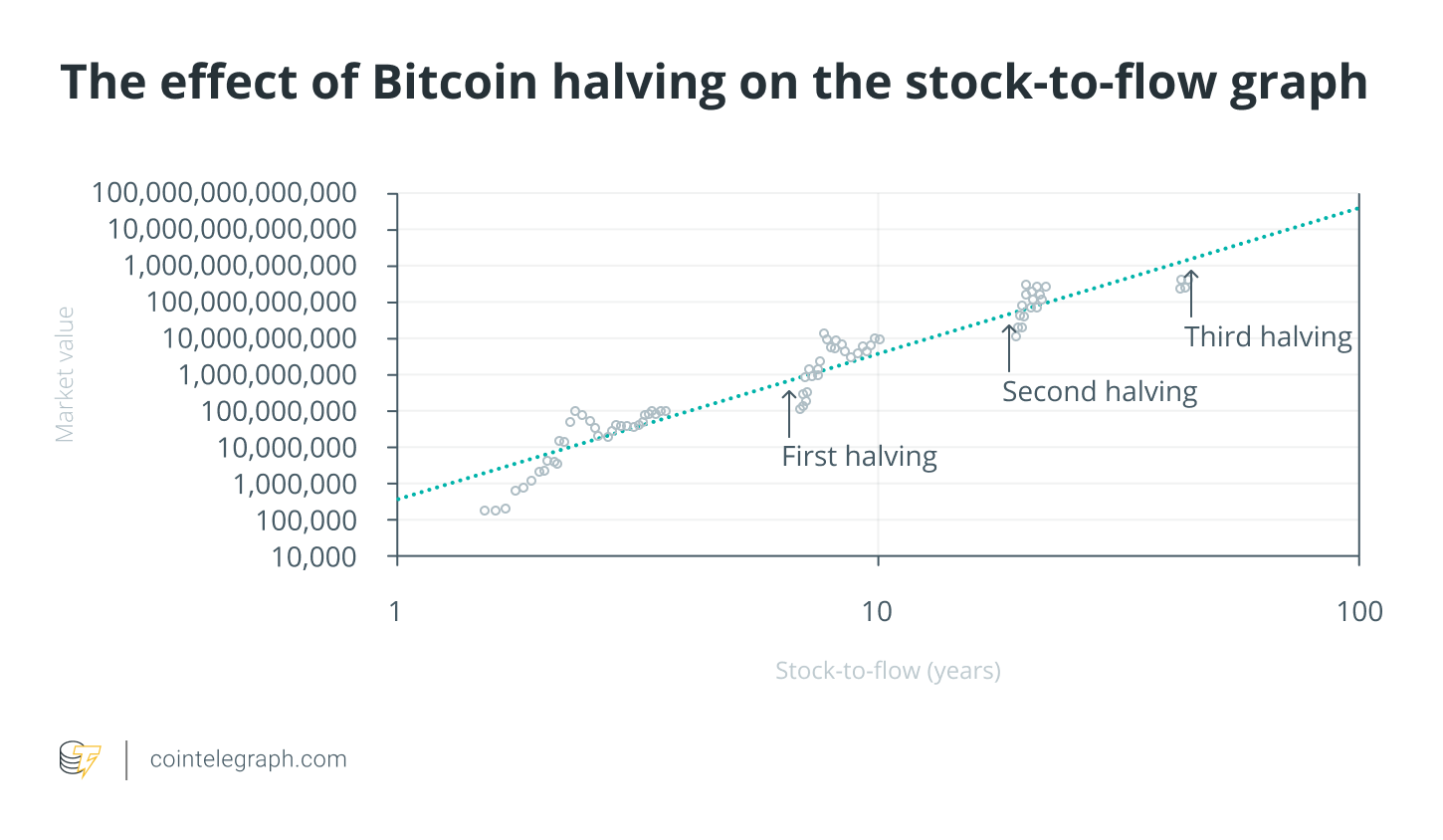

But how does this halving phenomenon impact the price of Bitcoin? Does the halving of the so-called “flow,” or the flow of new capital into the market, affect the price of Bitcoin itself? As we saw previously in the first part, Bitcoin seems to follow the stock-to-flow model; therefore, a reduction in flow, while maintaining the same stock, should correspond to an increase in price. Now that we’ve had three halvings, shouldn’t there have been as many bubbles?

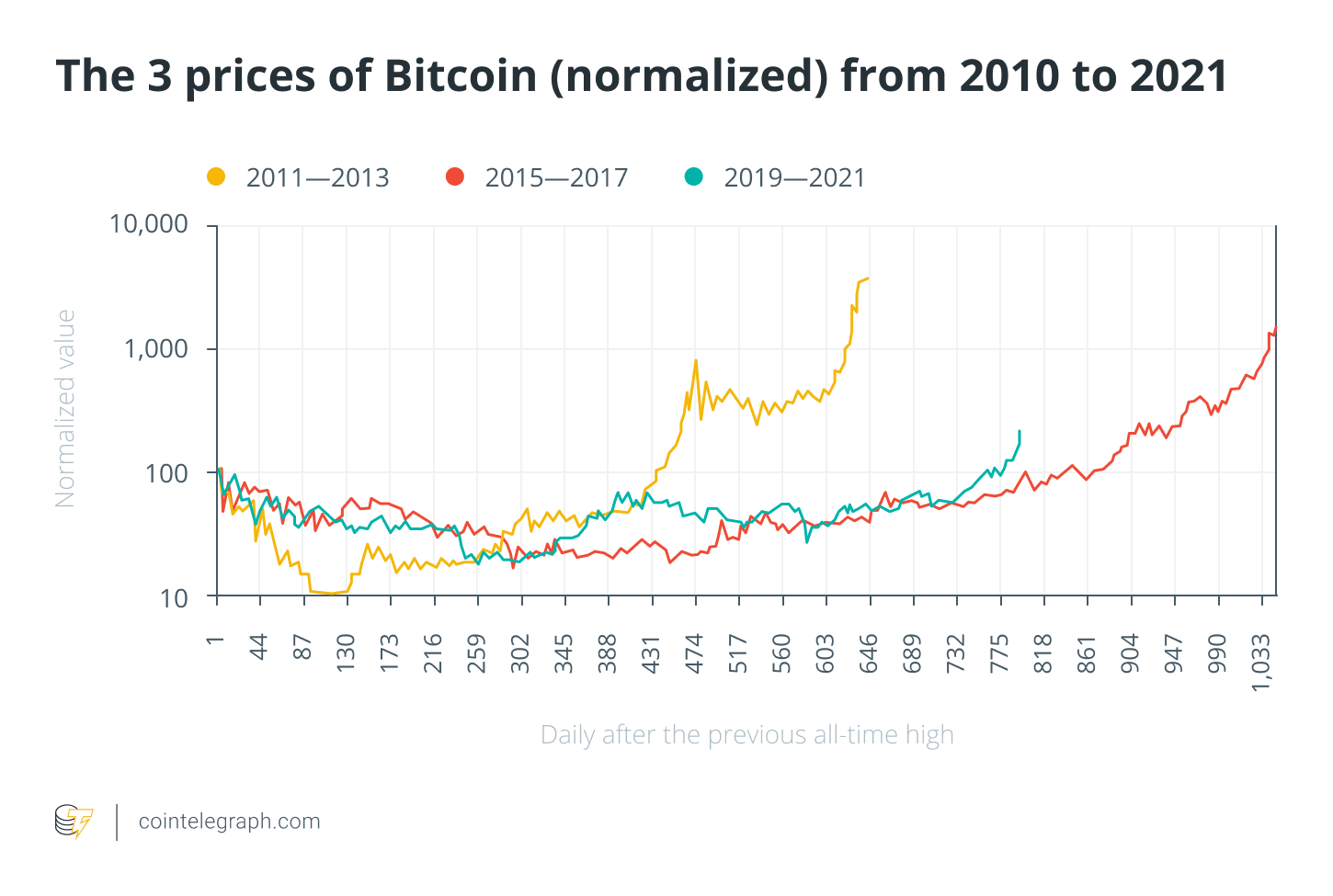

Do you know how many bubbles Bitcoin has had in its short life? Three fatalities. They are represented graphically below.

These are the three bubbles Bitcoin has faced so far, and each time the next maximum price became at least 10 times higher. Obviously, it is not a guarantee that it will do so in the future, but there are many factors that lead us to believe that what we experienced in 2017 will not be the last bubble — many more will follow in the future.

Can this information be used to determine a correct price for Bitcoin? Or at least, a potentially achievable price according to this model?

In fact, we can, if we take a look at this graph where the halvings are highlighted by jumps in the X-axis, in correspondence with the change in status of halving, we can estimate the fair value price — that is, the correct price at which Bitcoin could tend toward.

If the price of Bitcoin tends to return around the line described in the figure above, it is clear that we can estimate what the future target price of Bitcoin will be, based on the various halvings that await us.

From the graph, it is clear that the target price of Bitcoin is between $90,000 and $100,000. This information is very useful not only because it guarantees that we will arrive at those prices but because we should take into account our investment decisions, as it could actually get there and even exceed those price levels.

Obviously, these estimates must be taken as an intellectual attempt to understand the dynamics of Bitcoin and absolutely cannot be considered a suggestion or advice from the author. Understanding how Bitcoin can reach such values is not easy, and anyone approaching this fascinating world for the first time would have a hard time imagining how a seemingly worthless asset could have such a high price, especially if you fall into the trap of thinking of it as a dollar-par currency.

To do this, it is important to know its various aspects. One that is certainly fundamental for determining the price of Bitcoin is the adoption rate, which is to be described in the next part.

This article was co-authored by Ruggero Bertelli and Daniele Bernardi.

This article does not contain investment advice or recommendations. Every investment and trading move involves risk, and readers should conduct their own research when making a decision. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.

Ruggero Bertelli is a professor of financial intermediaries economics at the University of Siena. He teaches banking management, credit risk management and financial risk management. Bertelli is a board member of Euregio Minibond, an Italian fund specializing in regional SME bonds, and a board member and vice president of Italian bank Prader Bank. He is also an asset management, risk management and asset allocation advisor for institutional investors. As a behavioral finance scholar, Bertelli is involved in national financial education programs. In December 2020, he published La Collina dei Ciliegi, a book about behavioral finance and the crisis of financial markets.

Daniele Bernardi is a serial entrepreneur constantly searching for innovation. He is the founder of Diaman, a group dedicated to the development of profitable investment strategies that recently successfully issued the PHI Token, a digital currency with the goal of merging traditional finance with crypto assets. Bernardi’s work is oriented toward mathematical model development, which simplifies investors’ and family offices’ decision-making processes for risk reduction. Bernardi is also the chairman of investors’ magazine Italia SRL and Diaman Tech SRL, and is the CEO of asset management firm Diaman Partners. In addition, he is the manager of a crypto hedge fund. He is the author of The Genesis of Crypto Assets, a book about crypto assets. He was recognized as an “inventor” by the European Patent Office for his European and Russian patent related to the mobile payments field.

This article has been successfully submitted to the World Finance Conference.