You don’t have to be a professional football player to get a solid conk on the head. By one estimate from medical researchers, over 27 million people around the world sustain a traumatic brain injury every year. Some are from car accidents, others are from falls, or taking a header on the soccer field. But a growing body of evidence shows that even mild hits to the head can cause long-term damage and heighten the risk of neurological disease.

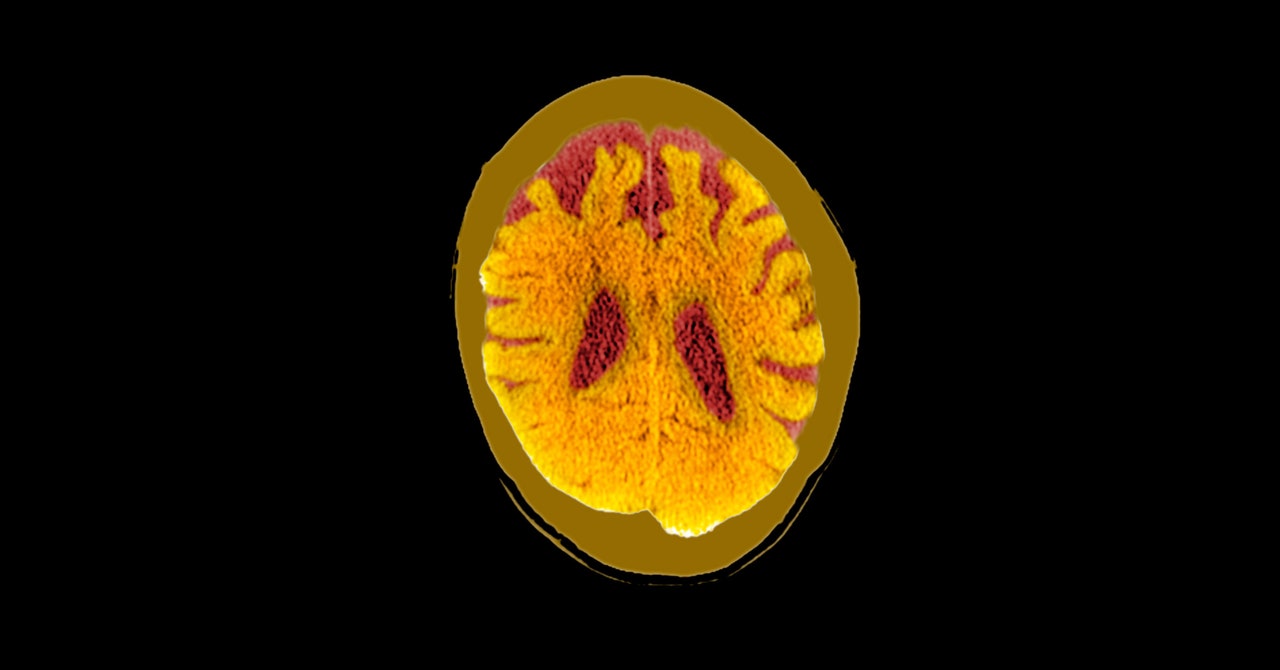

The brain is soft and usually cushioned from our skulls by cerebrospinal fluid. But when something hits the head hard enough, our brains get jostled and can smash into that hard bone, causing swelling or bleeding. That can lead to concussion symptoms like short-term memory loss or confusion. (Not every concussion causes people to black out or feel nauseous or dizzy.)

A new study published this month in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia draws from a large data pool tracking Americans whose health outcomes have been tallied for the last 25 years. The authors find that head injuries, even mild ones, are associated with a long-term increase in risk of dementia. The study also found that the more head injuries people sustain, the greater the risk of developing dementia.

Dementia is a general term for memory and cognitive losses caused by changes in the brain. The most common type is Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive and irreversible disorder in which tangles of proteins interrupt how neurons communicate with each other. But there are other types of dementia, including vascular dementia, which occurs when there isn’t enough blood flow supplying oxygen to the brain, and frontotemporal dementia, which is caused by a loss of cells in the front and side regions of the brain that can drastically alter personality and behavior.

The researchers hope that this new information will add to growing awareness about the implications of head injuries and the importance of preventing them. “That’s really one of the most important take-home messages from this study, because head injuries are something that are preventable to some degree,” says Andrea Schneider, a neurologist at the University of Pennsylvania and the lead author of the paper. “You can do practical things like wearing bike helmets or wearing your seatbelt.”

Previous studies have demonstrated a similar relationship between head injuries and dementia, but most focused on specialized populations like military veterans. Schneider says this study is one of the first to look at the relationship in a general, community-based population, which might be more representative of the average person.

Schneider and her colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania analysed data from over 14,000 participants in the Atherosclerosis in Communities study, an ongoing effort which has followed people between the ages of 45 and 65 in Minnesota, Maryland, North Carolina, and Mississippi since 1987. The study was meant to track the environmental and genetic conditions that might contribute to heart disease, but the researchers also collected medical records and asked participants to self-report any head injuries.

When the University of Pennsylvania researchers analyzed the data on traumatic brain injuries, they found that people who sustained one head injury were 25 percent more likely to develop dementia than those who did not. That risk doubled for those who had sustained two or more head injuries.

There are other health factors that could play a role, too. Genetics make some people more prone to dementia; some forms are heritable or accompany other progressive disorders like Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease. Other risks include vascular problems like diabetes and high blood pressure, environmental influences like pollution, and lifestyle choices like smoking. But Schneider says head injury is a significant factor. “We were able to say that about 9.5 percent of all cases of dementia in our study were attributable to head injury,” she says.