Nobody likes a frozen butt. So when François Haman attempts to recruit subjects to his studies on the health benefits of uncomfortable temperatures, he gets a lot of, well … cold shoulders. And he doesn’t blame them. “You’re not going to attract too many people,” says Haman, who studies thermal physiology at the University of Ottawa, Canada.

The human body is simply lousy at facing the cold. “I’ve done studies where people were exposed to 7 degrees Celsius [44.6 Fahrenheit], which is not even extreme. It’s not that cold. Few people could sustain it for 24 hours,” he says. (Those subjects were even fully dressed: “Mitts, a hat, boots, and socks. And they still couldn’t sustain it.”)

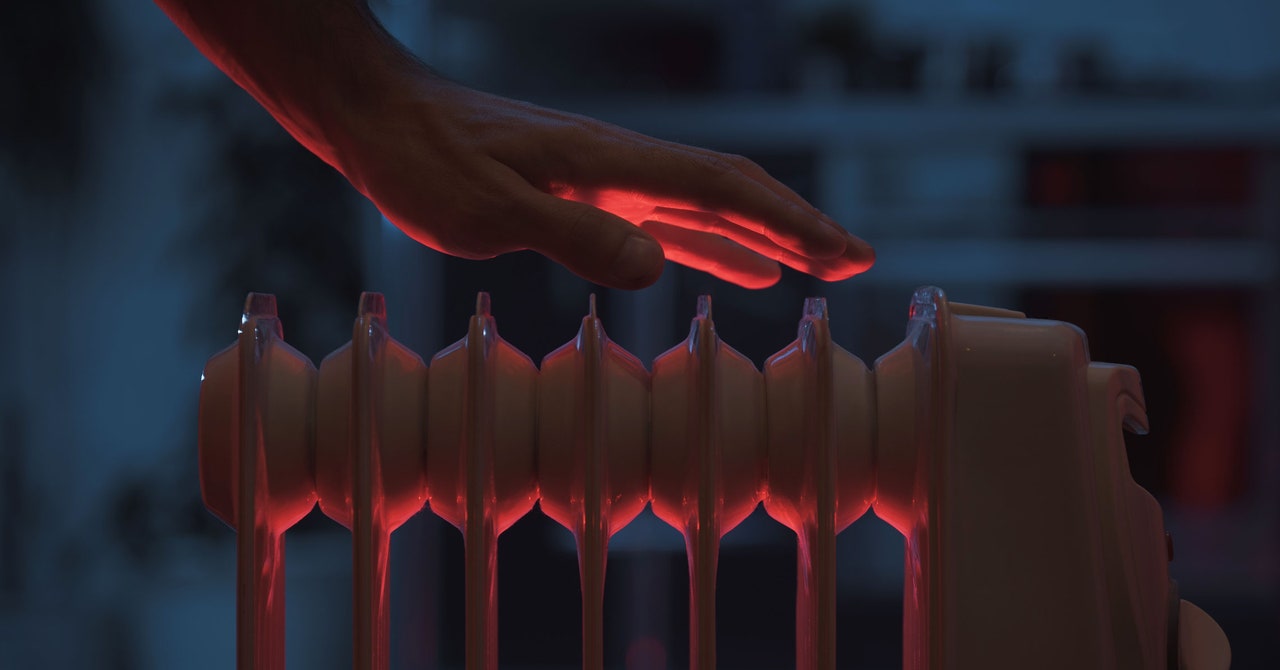

People strive to keep cozy or cool—not shivering, and not sweaty—by flattening temperature variations in indoor spaces. It’s easy to reach for the space heater or yell “Alexa, warm my ass up!” the moment you feel a touch of discomfort. But maybe you shouldn’t tinker so much with the thermostat. Some reasons for easing up on the heat are obvious: About 47 percent of American homes burn natural gas for heat, and 36 percent use electricity, which in the US is still mostly sourced from fossil fuels. And there may be other reasons to embrace the cold—health factors that physiologists like Haman have begun to uncover.

Before industrialization, says Haman, “these extremes were actually part of life.” Bodies dealt with cold in the winter and heat in the summer. “You kept on going back and forth, and back and forth. And this probably contributed to metabolic health,” he says.

Researchers know that your body reacts when it’s cold. New fat appears, muscles change, and your level of comfort rises with prolonged exposure to cold. But what all this means for modern human health—and whether we can harness the effects of cold to improve it—are still open questions. One vein of research is trying to understand how cold-induced changes in fat or muscle can help stave off metabolic disease, such as diabetes. Another suggests it’s easier than you might think to get comfortable in the cold—without blasting the heat.

To Haman, these are useful scientific questions because freezing is one of our bodies’ oldest existential threats. “Cold, to me, is [one of] the most fascinating stimuli because cold is probably the biggest challenge that humans can have,” he says. “Even though heat is challenging, as long as I have access to water, and to shade, I will survive fairly well. The cold is completely the opposite.”

“If you’re not able to work together,” he continues, “if you don’t have the right equipment, if you don’t have the right knowledge–you’re not going to survive. It’s as simple as that.” Figuring out how our bodies change in response to such a formidable and ancient opponent offers clues to how they work, and how they might work better.

Haman begins every day with a cold bath or shower. It’s a rush because the cold triggers the body to release hormones called catecholamines, which are involved in the fight or flight response. “I do have that sense of Oh my God, I’m feeling so strong, and I’m awake,” he says. “This is kind of my coffee.”