This story originally appeared on Hakai and is part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Dead fish were everywhere, speckling the beach near town and extending onto the surrounding coastline. The sheer magnitude of the October 2021 die-off, when hundreds, possibly thousands, of herring washed up, is what sticks in the minds of the residents of Kotzebue, Alaska. Fish were “literally all over the beaches,” says Bob Schaeffer, a fisherman and elder from the Qikiqtaġruŋmiut tribe.

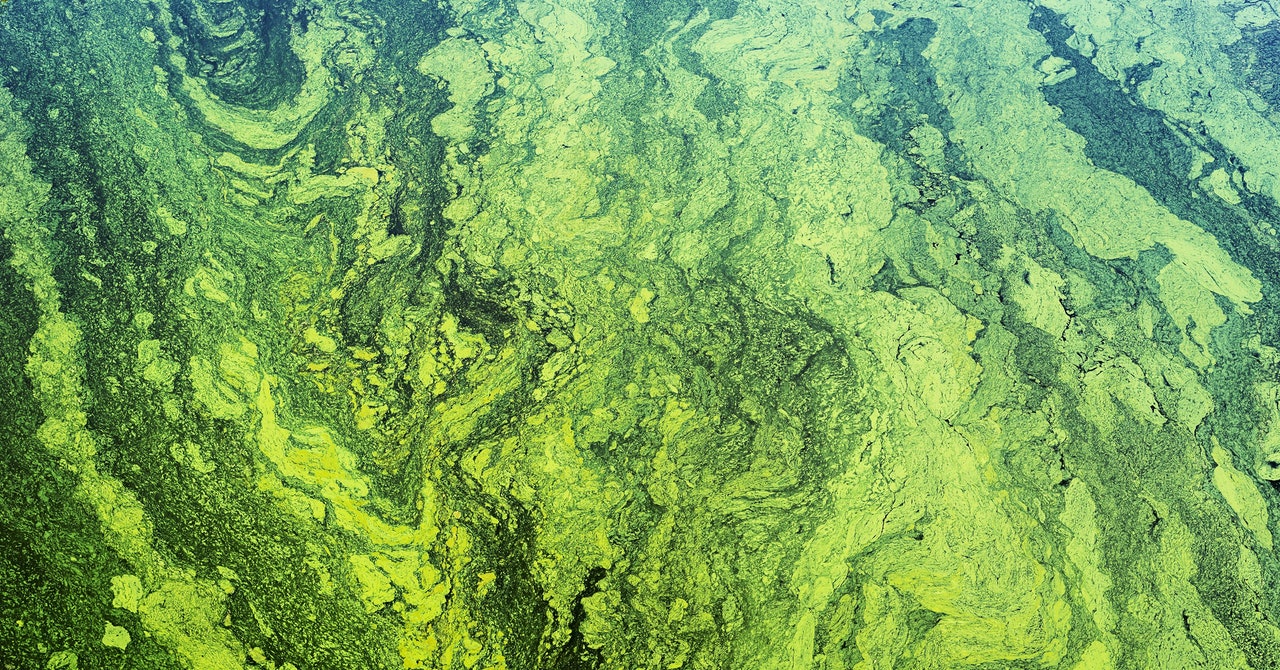

Despite the dramatic deaths, there was no apparent culprit. “We have no idea what caused it,” says Alex Whiting, the environmental program director for the Native Village of Kotzebue. He wonders if the die-off was a symptom of a problem he’s had his eye on for the past 15 years: blooms of toxic cyanobacteria, sometimes called blue-green algae, that have become increasingly noticeable in the waters around this remote Alaska town.

Kotzebue sits about 40 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, on Alaska’s western coastline. Before the Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue had his name attached to the place in the 1800s, the region was called Qikiqtaġruk, meaning “place that is almost an island.” One side of the 2-kilometer-long settlement is bordered by Kotzebue Sound, an offshoot of the Chukchi Sea, and the other by a lagoon. Planes, boats, and four-wheelers are the main modes of transportation. The only road out of town simply loops around the lagoon before heading back in.

In the middle of town, the Alaska Commercial Company sells food that’s popular in the lower 48—from cereal to apples to two-bite brownies—but the ocean is the real grocery store for many people in town. Alaska Natives, who make up about three-quarters of Kotzebue’s population, pull hundreds of kilograms of food out of the sea every year.

“We’re ocean people,” Schaeffer tells me. The two of us are crammed into the tiny cabin of Schaeffer’s fishing boat in the just-light hours of a drizzly September 2022 morning. We’re motoring toward a water-monitoring device that’s been moored in Kotzebue Sound all summer. On the bow, Ajit Subramaniam, a microbial oceanographer from Columbia University, New York, Whiting, and Schaeffer’s son Vince have their noses tucked into upturned collars to shield against the cold rain. We’re all there to collect a summer’s worth of information about cyanobacteria that might be poisoning the fish Schaeffer and many others depend on.

Huge colonies of algae are nothing new, and they’re often beneficial. In the spring, for example, increased light and nutrient levels cause phytoplankton to bloom, creating a microbial soup that feeds fish and invertebrates. But unlike many forms of algae, cyanobacteria can be dangerous. Some species can produce cyanotoxins that cause liver or neurological damage, and perhaps even cancer, in humans and other animals.

Many communities have fallen foul of cyanobacteria. Although many cyanobacteria can survive in the marine environment, freshwater blooms tend to garner more attention, and their effects can spread to brackish environments when streams and rivers carry them into the sea. In East Africa, for example, blooms in Lake Victoria are blamed for massive fish kills. People can also suffer: in an extreme case in 1996, 26 patients died after receiving treatment at a Brazilian hemodialysis center, and an investigation found cyanotoxins in the clinic’s water supply. More often, people who are exposed experience fevers, headaches, or vomiting.