With the Mars simulation, Haney suggests that NASA should watch the crew for danger signs, like symptoms of depression, heightened irritability, and moodiness, and changes in sleeping and eating patterns. And for the crew, he recommends creating routines, including social rituals, and trying to reach out to the outside world, not just to NASA’s mission control, to lessen the feelings of isolation.

For her part, Haston plans to bring along videos of familiar places and audio recordings of sounds and music that have meaning for her, anticipating the unsettling lack of sound in the simulated Mars environment. She also plans on using meditation to deal with anxiety.

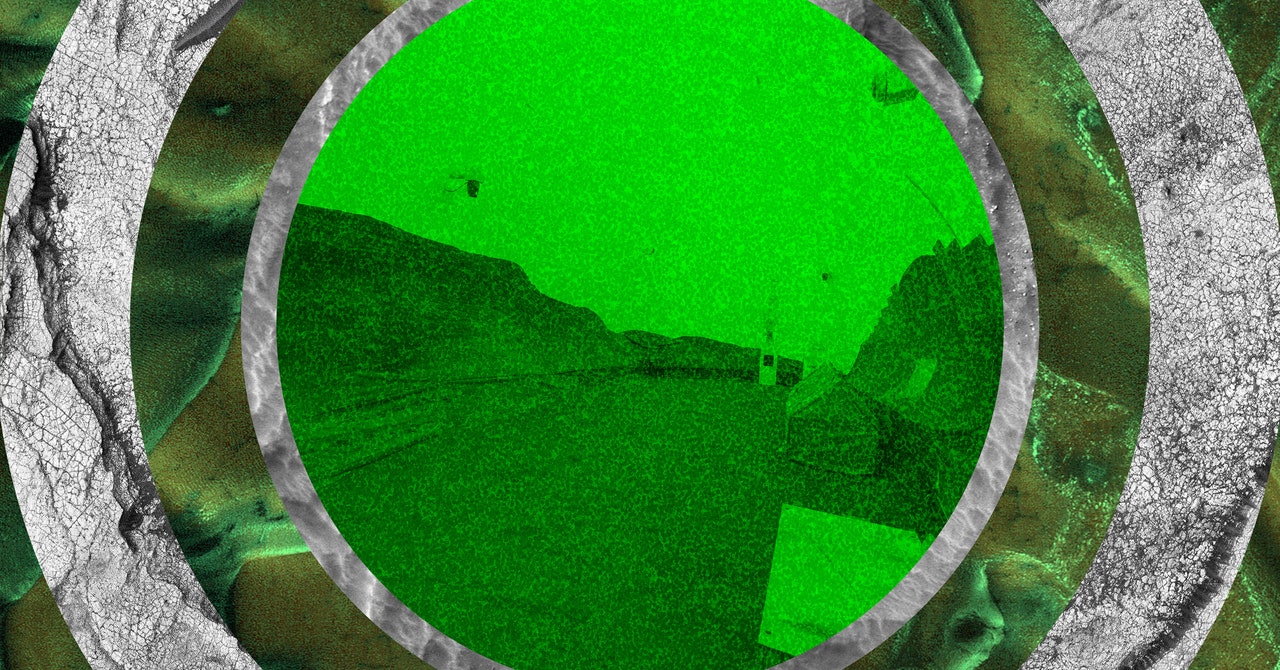

Chapea builds on previous Mars-like experiments, including the NASA-funded Hi-SEAS simulation on the northern slope of the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii. Hi-SEAS ran six experiments between 2013 and 2018, with the last one aborted after just four days when a crew member had to be taken to a hospital after suffering an electric shock.

Kate Greene, author of Once Upon a Time I Lived on Mars, was in the first Hi-SEAS crew, which lived in the habitat for four months. (One of her crewmates was Sian Proctor, a geoscientist and artist who later flew in orbit on SpaceX’s Inspiration4.) Greene thinks these programs are useful. “What makes them worthwhile is thoughtful experimental design,” she says. “I think it is of the utmost importance to consider the human factors involved in a long-duration space mission. As Kim Binsted, the head of Hi-SEAS, often said, ‘If something goes wrong psychologically or sociologically with the crew, it can be as disastrous as if a rocket exploded.’”

Ashley Kowalski, who served on an eight-month Mars simulation called SIRIUS-21 run by NASA and the Russian, French, and German space agencies, says they are also good for helping future crews psychologically prepare in advance. “Until you’re in that type of environment, you don’t really know how you’ll react to issues and situations that come up,” she says.

Ultimately, a real Mars mission will be much tougher than any simulation on Earth. Those astronauts will have to worry about threats like space radiation, the health effects of microgravity, and running out of water, food, power, and breathable air. And unlike the Chapea volunteers, if they get sick of their crewmates, they can’t just quit.

But Haston points out the positive side of this unique situation too. “There’s the negative people bring up: ‘You’re going to be four people getting on each other’s nerves.’ But we’re also going to become a tremendous unit that can do things and understand each other in a way that most people don’t have in their workplace,” she says. “You’ll be so dependent on each other, and also so close to each other. Seeing that outcome will be amazing.”