This story originally appeared in The Guardian and is part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A third of shark and ray species have been overfished to near extinction, according to an eight-year scientific study.

“Sharks and rays are the canary in the coal mine of overfishing. If I tell you that three-quarters of tropical and subtropical coastal species are threatened, just imagine a David Attenborough series with 75 percent of its predators gone. If sharks are declining, there’s a serious problem with fishing,” said the paper’s lead author, Nicholas Dulvy, of Canada’s Simon Fraser University.

The health of “entire ocean ecosystems” and food security is in jeopardy, said Dulvy, a former co-chair of the shark specialist group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The number of species of sharks, rays, and chimaeras, known together as chondrichthyan fishes, facing “a global extinction crisis” has more than doubled in less than a decade, according to the paper published September 6 in the journal Current Biology.

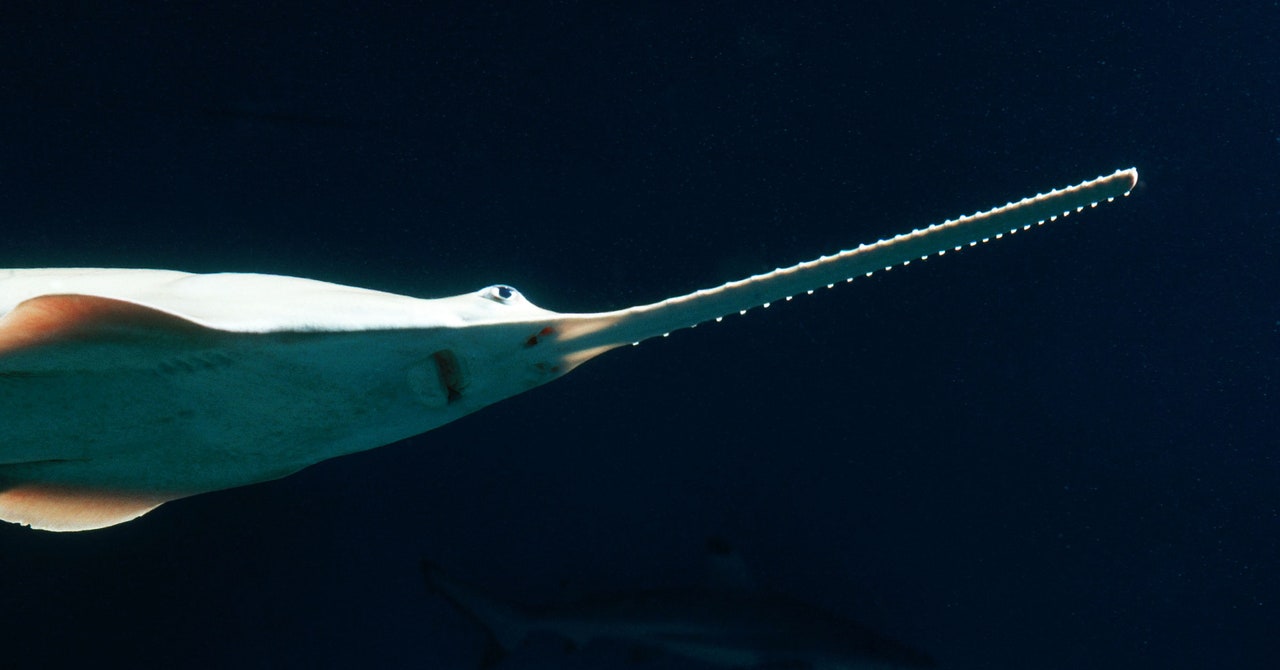

Rays are the most threatened, with 41 percent of 611 species studied being at risk; 36 percent of 536 sharks species are at risk; and 9 percent of 52 chimaera species.

Dulvy said: “Our study reveals an increasingly grim reality, with these species now making up one of the most threatened vertebrate lineages, second only to the amphibians in the risks they face.”

“The widespread depletion of these fishes, particularly sharks and rays, jeopardizes the health of entire ocean ecosystems and food security for many nations around the globe,” he said.

The assessment is the second to be carried out since 2014, and it comes after a study in January found shark and ray populations had crashed by more than 70 percent in the past 50 years, with previously widespread species such as hammerhead sharks facing extinction.

Sharks, rays, and chimaeras are vulnerable to overfishing because they grow slowly and produce few young. It has been estimated that 100 million sharks are killed by humans every year, overwhelming their slow reproductive capacity. Industrial fishing was a “key threat” to chondrichthyans, either on its own or in combination with other fisheries, the authors said.

Most of the sharks and rays are taken “unintentionally,” but they may be the “unofficial target” in many fisheries, the report said, and are retained for food and animal feed. Habitat loss and degradation, the climate crisis, and pollution compound overfishing, the authors said.

The species are disproportionately threatened in tropical and subtropical waters, especially off countries such as Indonesia and India, the experts found, because of very high demand from large coastal populations combined with mostly unregulated fisheries, often driven by demand for higher-value products such as fins.

Chondrichthyans have survived at least five mass extinctions in their 420 million-year history, according to the report. But, at least three species are now critically endangered and possibly extinct. The Java stingaree has not been recorded since 1868, the Red Sea torpedo ray since 1898, and the South China Sea’s lost shark has not been seen since 1934. Their disappearance would be the first time in the world that marine species have become extinct because of overfishing.

Colin Simpfendorfer, an adjunct professor at James Cook University in Queensland, Australia, said: “The tropics host incredible shark and ray diversity, but too many of these inherently vulnerable species have been heavily fished for more than a century by a wide range of fisheries that remain poorly managed, despite countless commitments to improve.

“As a result, we fear we will soon confirm that one or more of these species has been driven to extinction from overfishing—a deeply troubling first for marine fishes,” he said. “We will work to make this study a turning point in efforts to prevent any more irreversible losses and secure long-term sustainability.”