To prove that their probe could work, they tested it in both productive and unproductive soil. Both samples came from a large farm research site that already had thorough data for soil, crop, and terrain properties, including monitoring the nutrient composition and economic success of crops. Both were gathered from no-till farmland, had the same pH, and contained a substantial amount of organic matter. But there was one key difference: The productive soil had a higher wheat yield.

Well, make that two differences: When the researchers tested their probe, the productive soil generated an electric current, reaching a maximum of 34.4 microamperes after about three days. The unproductive soil generated almost none at all. (Its current was about 1 percent of the productive soil’s.)

“I was definitely surprised and excited, especially when we did another set of replicates and found the same results,” says soil scientist and study coauthor Maren Friesen.

Their probe has two main parts: The part that goes in the soil is made of carbon fabric electrodes, flexible pieces of fabric with copper and titanium wires sticking out of them. Each looks almost like a computer mouse pad. These hook up to a larger device called a potentiostat, a box about the size of a layer cake, which measures current.

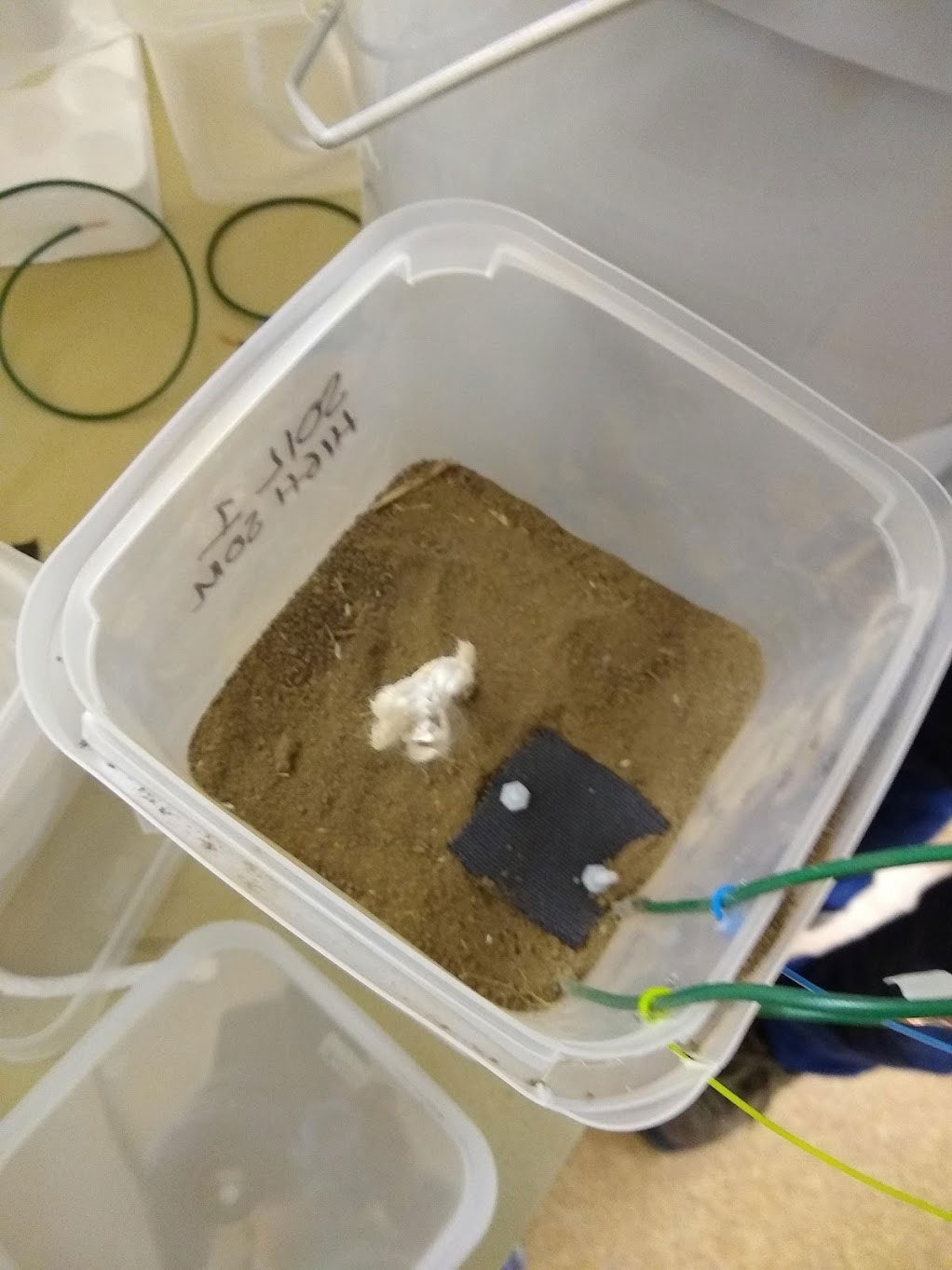

For their test, they sieved dry soil into a 48-ounce container, placing the electrodes at different depths in the soil. After they placed one electrode, they covered it with another couple centimeters of soil, and then placed another. Then they used the potentiostat to read out the voltage results on a computer.

As a secondary measure, they also used scanning electron microscopy to take very high-resolution pictures of the carbon cloth electrodes. These images revealed a much more dense microbial growth on the electrodes that were in the healthy soil. While those microbes covered the carbon fiber like moss growing all over a tree, the microbes from the unhealthy soil presented more like a small patch.

Carbon fiber electrode being placed in a soil mesocosm for soil electrochemistry measurements.

Photograph: Maren Friesen

“Soil has been described as ‘the final frontier‘ for understanding microbial diversity, because it is so heterogeneous and the microbial communities are so complex,” says Friesen, referring to a 2010 article by Alistair Fritter, a now-retired ecologist at the University of York. Fritter’s article argued that, while humans devote a lot of time and resources to preventing animals from going extinct, people are likely not even aware of all the species in soil that might be at risk.