One day Joe Morrison, the vice president of a satellite company, gave members of his team a strange task: Go buy images from another company’s picture-taking spacecraft. He wanted to see how easy it was to exchange money for those orbital goods and services. So the group scampered off and ordered a satellite image of an area in Southeast Asia, to be taken within the next three weeks. They paid around $500. Easy.

Three weeks later, though, they’d only gotten radio silence. It turned out that the company had been unable to take a snap, and the broker had canceled their order. It was a high-demand area, of which many people wanted portraits. Plus, it was monsoon season, when clear shots were hard to come by. So instead, the company had tasked their satellite to take the image sometime within the next year.

… Thanks?

To Morrison, this experience demonstrated much of what’s wrong with the “remote sensing” industry. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but that’s true only if you can get a shot in the first place. Clouds cover, on average, about two thirds of Earth. And at any given time, roughly half of the planet is dark. (This area’s experience is commonly referred to as “night.”) In either of those conditions, traditional satellite imagery is not worth many words at all. And if you want to buy many photos of the same area, tracking how things change, this gets difficult and expensive—unless you’re a defense department or spy agency with deep pockets and front-of-queue influence. That’s why Morrison hopes data from his employer—a company called Umbra, based in Santa Barbara, California—could fulfill what has long been remote sensing’s promise: The ability to monitor Earth, not just take infrequent static photographs of it.

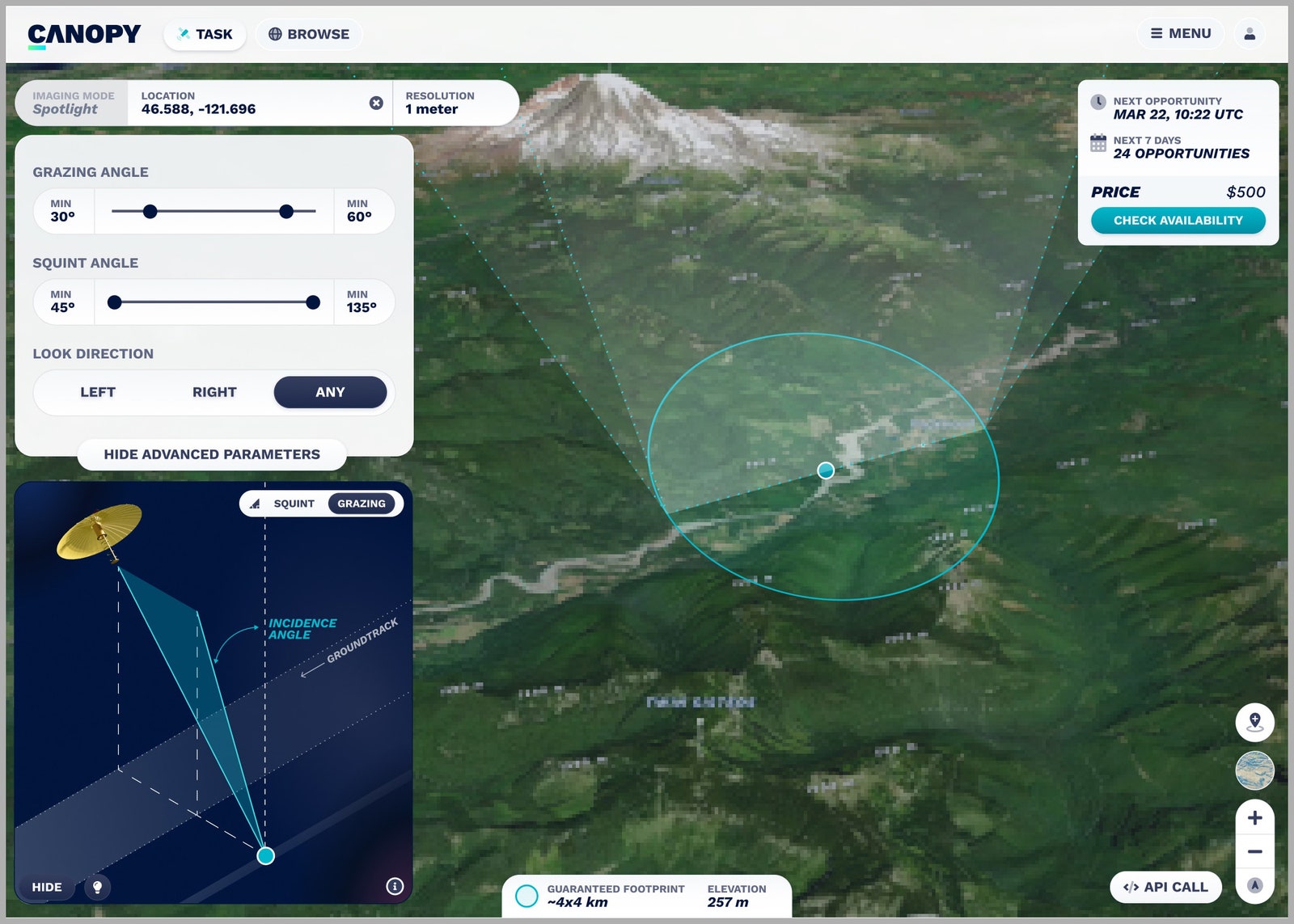

Courtesy of Umbra Lab Inc.

Umbra’s satellites don’t take pictures, anyway; they take “synthetic aperture radar” (SAR) data, which functionally means “radar data from space.” It works like this: A satellite shoots microwaves toward the planet, then waits for their echoes to bounce back up. Because the satellite will have orbited to a slightly different spot between the radar’s emissions and returns, it effectively functions as an antenna as big as that distance—a “synthetic aperture.” Objects with different makeups reflect the microwaves differently—a building, for instance, behaves differently than an ocean. And objects at different distances from the satellite take different amounts of time to whip the waves back spaceward. So by using SAR, analysts can get some pretty sharp detail on shape, size, and even composition.

Most important, microwaves shoot straight through clouds and don’t know the difference between day and night. SAR satellites, then, can observe Earth in any weather, at any hour. That capability is proving particularly useful to those who want to track events that tend to happen during overcast conditions and under cover of darkness: floods.

Flooding has long been the cause of human suffering—it destroys crops, livestock, infrastructure, and human lives. Climate change is increasing flooding risk, since extreme weather events and sea levels are on the rise. According to professional services firm Marsh McLennan, which specializes in risk assessment, since 1980 there have been around 4,600 floods worldwide, which together have cost more than $1 trillion in damages, or around 40 percent of the world’s total natural disaster losses. Severe floods are public health hazards, like 2020’s monsoon flooding in India, which killed 1,922 people—the year’s most fatal natural disaster, unless you count Covid. Worldwide, floods killed more than 6,000 people that year, according to the Global Natural Disaster Assessment Report.